Lucy Dever, Collections Specialist

We don’t tend to give the mail a lot of thought these days. With email, cellphones, and especially the internet, so-called “snail mail” is increasingly neglected, fit only for low-stakes correspondence like birthday cards or letters to Santa. But once upon a time, the mail was all-important, the lifeline connecting anyone who lived farther than a few miles’ walk.

Though it may no longer serve as our primary means of communication, the mail still brings us something that electronic messages can’t—tangible human contact. Think about that birthday card you still have in your drawer, the one with your grandma’s signature that you run your fingers over from time to time. Or the letter from a childhood pen-pal, yellowed with age but still fresh in your memory. These things are precious, physical reminders of our connection with people who are absent from us. The mail, though it may seem archaic and irrelevant in our modern world, fosters family and community—just like the Shakers.

Functional Elegance

Earlier this week, the US Postal Service released a collection of twelve stamps in honor of the 250th anniversary of the Shakers’ arrival in America in 1774. The collection, titled “Shaker Design,” focuses not only on the beauty of Shaker craftsmanship, but also on the practical use of these objects by real people, for real working tasks. The stamps celebrate this “functional elegance” on large and small scales, from the smallest corner of a handkerchief to the expansive façade of a family dwelling. One even features the famous double spiral staircase of the Trustees’ Office here at Pleasant Hill, designed by Micajah Burnett in 1839.

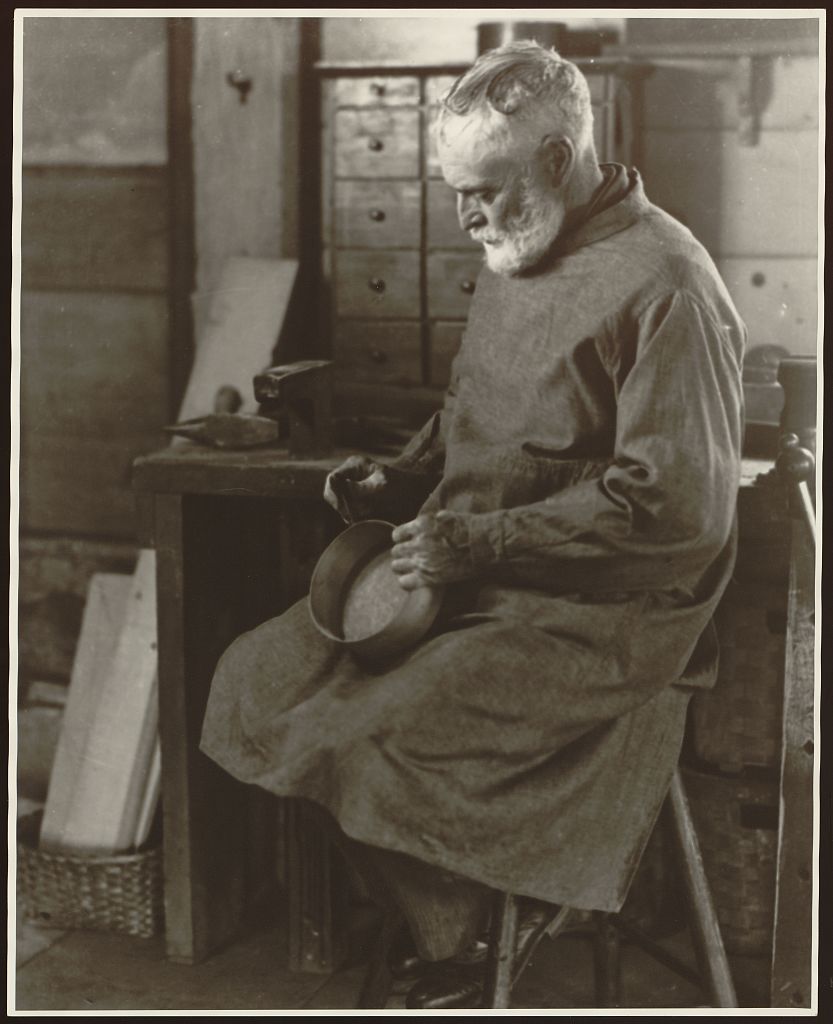

The collection’s “selvage,” or backing paper, ties these twelve seemingly disparate images together with a photograph of Shaker Brother Ricardo Belden crafting oval boxes in his workshop at Hancock Shaker Village, circa 1935. The photo is striking, giving a face to these objects handcrafted long ago.

But an emphasis on human connection is far from the only thing linking the Shakers to the Postal Service. In fact, the two have a long and deeply connected history—especially at Pleasant Hill.

Celerity, Certainty, Security

The United States Postal Service was founded by the Second Continental Congress in 1775, predating the Declaration of Independence by nearly a year. Instrumental to the Revolutionary cause and indispensable to citizens of all kinds, the USPS expanded significantly westward in the late eighteenth century, and Kentucky’s first post office was established in Danville in 1792. Harrodsburg followed shortly after in 1794, giving Mercer County residents access to reliable communication networks for the first time. Mercer County’s second post office, however, was established in the spring of 1818, right here at Pleasant Hill.

The founding of the Pleasant Hill Post Office came just after the introduction of a major innovation to mail services in the Bluegrass: the stagecoach. Stagecoaches, so named because they carried out their journeys in different stages with different horses, could carry correspondence at around eight miles per hour, especially if they had macadamized, or hard paved, roads to drive on. After the introduction of the mail stagecoach in Kentucky in 1816, constructing these macadamized roads became a top priority for the young state.

In 1833, the Kentucky legislature called for the construction of a paved turnpike connecting Lexington, Harrodsburg, and Perryville to facilitate easier trade, travel, and communication. The proposed route ran through the heart of Pleasant Hill, and the Shakers quickly got to work on their portion of the new macadamized road. Spearheaded by Micajah Burnett, Pleasant Hill’s engineering wunderkind, the new turnpike was completed by 1839, and quickly became an integral part of postal services in the region.

A Rising Star (Route)

When Lexingtonian William T. Barry was appointed Postmaster General in 1829, he quickly began working on “the great mail development,” a project which would increase the reach, speed, and reliability of postal service on what was then just short of the western frontier. At the start of this venture, all mail from the eastern states was carried westward on the Cumberland Road, running from Maryland to Missouri. But soon Barry began to plan a new route into the south, branching off from the Cumberland Road in Zanesville, Ohio. This route would showcase the efficacy and potential of the mail coach—and it would run right through Pleasant Hill.

Known as the Zanesville-Florence Star Route, the road began in Zanesville, Ohio, then on to the ferry at Maysville, then stopping in Lexington, Harrodsburg, Perryville, Lebanon, Campbellsville, Glasgow, Gallatin, Nashville, and Columbia before terminating in Florence, Alabama. If a letter was destined for an address even further south, it could be taken on board a steamboat and delivered all the way down to New Orleans.

Partly conceived to facilitate this new route, Pleasant Hill’s new turnpike, with its smooth macadamized surface, was an ideal road for mail coaches. These vehicles, pulled by teams of four to six horses, were the dominant means of mail delivery in the US for nearly forty years. They only began to decline in the mid-1850s, when railroad technology had improved enough to overtake the stagecoach in both speed and efficiency. The route through Pleasant Hill was discontinued by 1877, and the post office followed in 1904.

While the mail coaches may be gone along with Pleasant Hill’s Shakers, the need for communication and connection to each other persists, beyond what’s possible in an intangible, typed message. So, this summer, why not do as the Shakers did—slow down, take a deep breath, and send a letter to someone you love.

And when you do, imagine the sound of hoofbeats.

The Shaker Design Stamp Collection can be purchased online here, onsite at Shaker Village’s Shops or at your local Post Office.