Alli Bramel, Collections Specialist

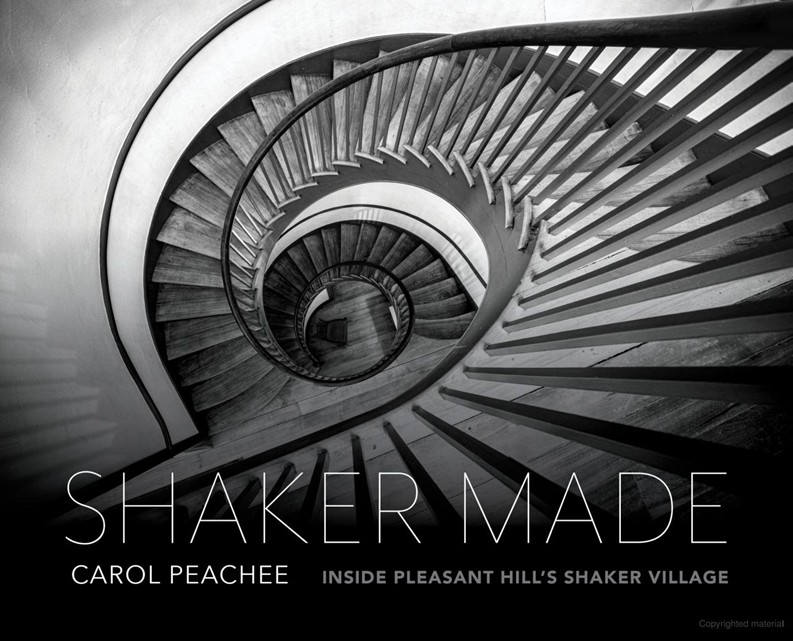

Lexington photographer Carol Peachee has photographed Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill for more than four decades. Later this month, an exhibit of selected works from her book, Shaker Made: Inside Pleasant Hill’s Shaker Village, will be on display in the Centre Family Dwelling.

Image courtesy of The University Press of Kentucky, 2024.

We spoke with Carol over the phone about her work as an artist, her time spent photographing the collections at Pleasant Hill, and what she hopes visitors take away from her project.

Tell us about your background and how you got your start in photography. How long have you been an artist?

I received my first camera at the age of sixteen and set up my very first dark room around the same time. In the beginning, I used my camera to document everyday moments, much like many others do. My interest in photography deepened when I spent a year in Europe through my college’s abroad program, during which I took a photography class with Janine Niépce. Janine, related to Joseph Niépce—one of photography’s pioneers—became more of a mentor than an instructor, as the class consisted of just the two of us working closely together. It was during this mentorship that I first realized photography could serve a larger purpose: to tell a story, capture a mood, and have a meaningful impact.

It wasn’t until 2005 that I was comfortable calling myself an artist, when I first received encouragement from others who viewed my work and suggested I publish it. Before then, my photographs were captured for personal satisfaction. Afterwards, while I continued to photograph for myself, I also began considering how my images could be shared publicly. I started submitting my work to art shows, won awards, and eventually published my first book in 2015.

You’ve photographed Pleasant Hill for over four decades. What was the initial thing that drew you to Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill? Why the Shakers?

My upbringing in Richmond, Virginia included frequent visits to Colonial Williamsburg and other historic locations as they were being restored for public appreciation. This early exposure sparked a lifelong interest in history and cultural sites. My connection to Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill began after I moved to Kentucky for graduate school. When I first visited Shaker Village, I was immediately struck by its atmosphere, reminiscent of Williamsburg, yet distinctly unique. My curiosity led me to learn more about the Shaker community, their beliefs, commitment to equality, and social justice values, even before such terms were used. The monastic, utopian qualities of the community resonated deeply with me and reflected many of my own values, creating a lasting connection that drew me back over the decades.

Walk us through your planning process for capturing the images that came to be included in your book Shaker Made: Inside Pleasant Hill’s Shaker Village. How was this process different from other projects you’ve worked on in the past?

This project was completely different from my past projects. In past projects, I was photographing abandoned distilleries or sites, or I was searching out and photographing historic barns. Mostly I was alone in determining what was to be photographed, and how to interpret the site. At Shaker Village the photographic experience was more interactive with others. Initially, in the 1990’s, the Village was set up as living history with the collection curated as a display and people dressed in period costumes acting as interpreters. When I photographed then I was limited by how the “set” was arranged and the area I was allowed in. Since that time, the material collection has been maintained as a museum collection in a temperature-controlled facility. To photograph the items in the collection required I work closely with the Collections and Education Director, Becky Soules. This began a collaborative process that was very different from past projects for me. For example, I might tell Becky that I wanted to photograph things that could be metaphorically linked to spirituality, and she would provide different options from the collection to work with. Eventually, I started asking for specific things. I would maybe ask, “Do you have wood working tools?” and Becky would pull a representation of those types of objects from the collection. This book wouldn’t be the book it is without Becky. It was an extremely collaborative experience between the two of us. I went from doing completely solitary photographing experiences in my other projects to an extremely collaborative experience.

A crucial aspect of your work is to bring awareness to cultural and natural heritage sites. How do you hope your photographs will impact the understanding of Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill as a cultural heritage site?

Well, there are layers to this answer.

Superficially, I like to document in a way that makes people want to look at things that are disappearing. I want to stimulate thinking about how those things reflect how we have lived in the past. Where we came from matters. In my work as a psychotherapist, I always go back to where people come from. Where we came from and how we did things mattered. But I don’t want to just document it. I want people to pause and have an emotional response. An emotional response may make them care and think about saving these things.

Another layer is related to the shift away from living history in presentation of material goods and the availability of access to items in a collection. I want to stimulate readers to consider history in a live way. As a child at Williamsburg, I would get to stand in historic places and try and image life during those times. The interpretations helped. That made me appreciate the connection of humanity through time. My hope is my books can present the collections with a certain amount of interpretation that might stimulate the same consideration of history. I also hope to help stimulate an even younger generation. I actually put my books in the waiting room in my office and kids will flip through them and look at the pictures and ask questions.

Do you have a favorite grouping of photographs you captured during this project? Was there a particular artifact or building that was your favorite to capture?

There are 3 different styles of images of the Trustees’ Office staircase that are among my favorites. I have them hanging in my dining room at home. I like this grouping because there’s one that is modern and angular, one that is very soft and traditional, and one that is playful. Although it’s the same staircase, it has many different perspectives. You can come back repeatedly and see it differently each time. It’s dynamic, not static. As people look at it over time, they’ll see something different. The second photo is like a film one I took in the 1990s.

I also like the image of textile draped over the back of a chair. The textile is pink, but I have the black and white image in my house. There’s something very familiar to me about that image.

What is your editing process like taking your captured images to black-and-white? What is the process like to take those black-and-white photos back to color for this exhibit?

I process the image first in color and get it close to what I might like as a color image. I supersaturate it to then translate it into black-and-white and play with contrast and light. Knowing what will happen when you translate it helps. Knowing what red, green, or yellow will look like in black-and-white.

Then I utilize color information to desaturate and create the black-and-white rendering. This process is itself a form of artistry. Even if the same original image were provided to three different artists, their outcomes would inevitably vary.

Taking an image from color, to black-and-white, and back to color are three different processes. Sometimes, I go back to the first color image I took and work off that. Other times I’ll start from the black-and-white photo and reprocess it back to color. At each stage, there are artistic decisions to make.

Is there anything else you’d like to share with us about your hope for this body of work and what you hope visitors will take away from this exhibit?

I hope people who look at the photos can see more than objects. I wanted to create an emotional response to how the Shakers lived. For example, I hope people see not just a pair of shoes on the floor. When people look at those shoes, I hope they can imagine a Shaker sister sitting in the Meeting House wearing these shoes during service. Shoes of silk that might have been made of silk spun right here at Pleasant Hill. I want people to think about the people’s lives behind these objects, not just the stuff.

What’s interesting is how the Shakers’ philosophy and their lived lives became integrated into their objects. These objects were not made to be beautiful but were beautiful because they were infused with their philosophy and spirituality. The objects are beautiful not because the Shakers wanted to have pretty things, but because they made their objects for a higher power. The beauty was a biproduct. Hands to Work Hearts to God.

The exhibition, Shaker Made: Carol Peachee’s Photography of Pleasant Hill, will open on July 19, 2025, and be included with general admission to Shaker Village through November 9, 2025. Carol Peachee will sign copies of her book Shaker Made: Inside Pleasant Hill’s Shaker Village, and copies of the book will be for sale during the opening on July 19th.