Laura Baird, Stewardship Manager

The monarch butterfly is one of the most celebrated insect species in North America and a flagship species for grassland conservation. Like many insects, monarchs have suffered steep declines in recent decades due to habitat loss. This is further complicated when considering monarch habitats stretch from southern Canada to central Mexico. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) formally declared monarchs to be an endangered species in late July. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, nearly one billion Monarchs have been lost in overwatering sites in Mexico since 1990!

Each February, monarchs emerge from their overwintering grounds high in the forests of central Mexico and fly north, mating and laying eggs on milkweed as they go. Several generations of monarchs go through their life cycle while repopulating most of the United States and the southern portions of Canada.

Monarch Life Cycle

- Eggs hatch in about four days.

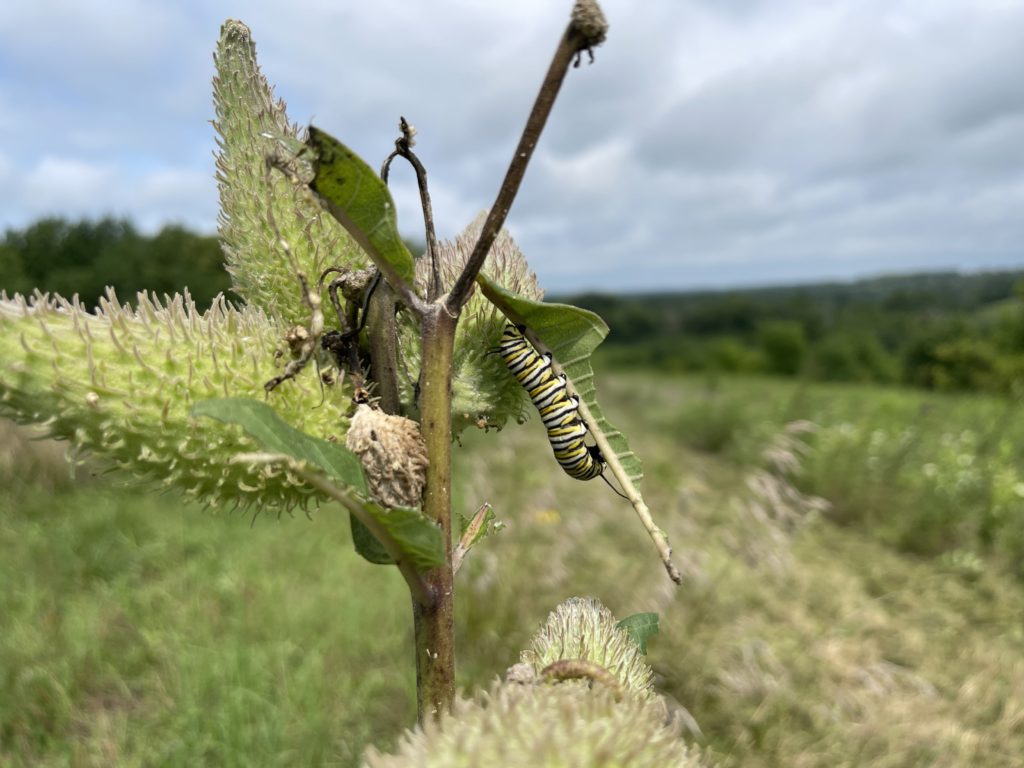

- Caterpillars emerge and eat milkweed for two weeks.

- Caterpillars transform into a chrysalis and hang for ten days.

- An adult monarch butterfly emerges, feasts on nectar and looks for a mate for two to six weeks.

The Next Generation

The monarchs we’re currently seeing are considered the fourth generation of the year, and their lives are a bit different from the previous three generations. This generation, born in September and October, are currently migrating south, back to the Oyamel Fir forests of central Mexico. The monarchs born here at Shaker Village travel over 1,500 miles to join millions of other monarchs from across North America, where they will then rest together for six to eight months before flying north and restarting the process next year.

Here in the United States, modern agricultural practices and development has led to a loss of both milkweed, the only food source of monarch caterpillars, and fall wildflowers, which adults need to fuel their journey south at this time. Their overwintering grounds in Mexico have also been impacted by expanding agriculture. Climate change has also threatened the species, creating more frequent droughts, floods, and intense storm events that threaten the plants monarchs rely on throughout their range.

Research is Key

A number of nonprofits are doing their part to protect monarchs and collect more data to learn about their complex lives and migratory patterns. One of the largest monarch-specific nonprofits is Monarch Watch at the University of Kansas. They run the Monarch Waystation program, dedicated to increasing monarch habitat in the United States, whether it be on a large scale (the entirety of Shaker Village’s prairies are registered as a Monarch Waystation!) or in your own backyard (you can visit our small demonstration Monarch Waystation beside the Meeting House).

Monarch Watch has also run a monarch tagging program since 1992. The tags are small stickers applied to a hindwing. When tags are recovered (usually after the insect’s natural death), the code on that tag identifies the butterfly and where it came from. The monarch tagging program is providing data to answer several key questions about the timing of migration and mortality ratios regarding size and origin of the butterflies. Recovering tags is difficult and rare, but a butterfly tagged in The Preserve at Shaker Village in 2015 was recovered the next year in El Rosario, Mexico the next year! We continue to tag monarchs in cooperation with Monarch Watch each year in hopes our efforts can contribute to the overall success and hopeful resurgence of these regal butterflies.

How to Help

If you’d like to help then we encourage you to join our Monarch Butterfly Tagging workshop at the Village on October 1. We’ll take an easy hike through The Preserve and learn how its wildflowers serve as an important habitat for butterflies and other essential pollinators, then help tag monarchs to track and monitor their annual migration.