The role of African American Stonemasons in the Bluegrass.

Pony Meyer, PhD, Program Specialist

Em J Parsley, MFA, Village Interpreter

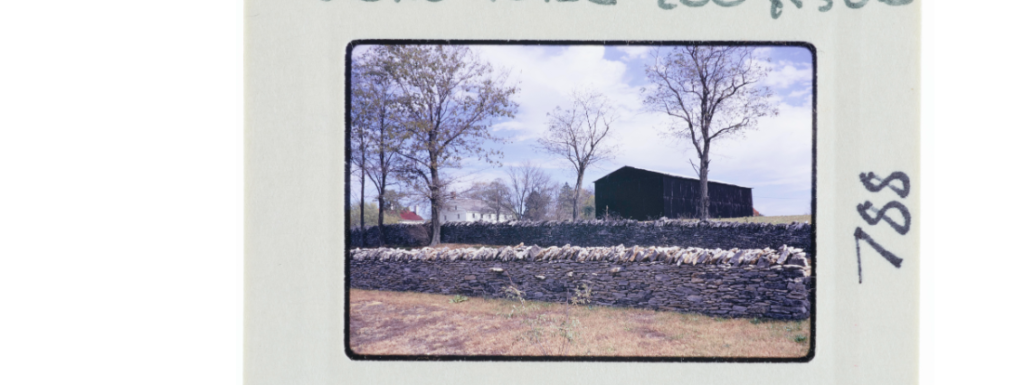

Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill was once home to 40 miles of dry-stack rock fences. Today, we maintain 25 miles of these beautiful historic rock fences. Most of them were built during a 15-year period between the 1840s and 1850s.

Like most of the historic rock fences in the Bluegrass region built before the 1860s, these were engineered by expert masons of Irish descent. But they were not the only ones involved in building these rock fences. African Americans played a crucial role as well.

Some people call these fences “slave fences,” but this is a bit of a misconception. There is some truth to the name—enslaved people were part of the workforce assisting Irish stonemasons. However, after emancipation, free African American masons also played an important role in constructing these iconic features of Bluegrass landscapes.

At Pleasant Hill, it is certainly possible that enslaved African Americans assisted in building our rock fences. We do consider the Shakers emancipationists, and Pleasant Hill Shakers purchased the freedom of several enslaved African Americans. We know of at least 21 African Americans who lived here equally as spiritual brothers and sisters. The Shakers never enslaved people, and because they did not believe in personal ownership of property, enslavers were prohibited from formally joining the community.

However, the Shakers at Pleasant Hill did use the labor of enslaved people from surrounding enslavers. Rock fence building was hard work and took many hands. It is therefore possible that enslaved African Americans were part of the workforce for building these fences here at Pleasant Hill.

Elsewhere in the Bluegrass, this was certainly the case, especially on large plantations. In a letter addressed to Woodford County in 1840, for example, a landowner’s son asked “if the [enslaved people] were going to have enough stone hauled in for the new fence so the immigrants could start as soon as the ground settled in the spring.”

Farm records and African American oral traditions also indicate that enslaved people were involved in building these fences. During the antebellum period, they gathered and hauled rocks from quarries to construction sites and dug fence-foundation trenches.

As African Americans worked to assist Irish masons in construction, they eventually acquired the skills to become rock fence masons themselves. The skills, knowledge of tools, vocabulary, and techniques were then shared and passed down through the generations. However, it is difficult to know how many enslaved men were working as stonemasons before the Civil War because the census did not list the occupations of enslaved people.

After emancipation in 1863, however, we know that many of these laborers became accomplished stonemasons and started contracting their own work. Some started their own businesses. In fact, after emancipation the number of African American stonemasons started to increase while the number of Irish stonemasons started to decrease.

In 1870, for example, there were seven African American stonemasons compared to zero Irish in Mercer County. That same year in Boyle County, there were twenty-eight African American stonemasons and two Irish. By 1910, most stone fences in the Bluegrass were built by African Americans.

The Guy family provides us with one such example of five generations of stonemasons in the Bluegrass. Henry Guy, while still enslaved, helped build a rock fence between Shelbyville and Clay Village, a fence that his grandson, John H. Guy, would be responsible for relocating and rebuilding in 1941. The Guy family constructed several other prominent rock fences in the Bluegrass region, including those on the Walmac and Elmendorf farms.

The most recent stonemason in this line, John H. Guy III, is experienced in both dry-laid and mortared construction. In a 1989 interview, Mr. Guy provided some unique insights into the talent necessary for rock fence building, particularly for farm field fences and reconstruction of aged fences. He observed that a senior mason could discern after just a couple of hours if the trainee had the potential to do good-quality work at a rate quick enough to make a living. After all, rock fence masons are still paid by the foot or the rod, not by the hour.

Mr. Guy highlighted the necessary skill of identifying the rock that best fits the space among piles of many differently sized rocks. The mason must further be able to envision how two or more rocks will fit together either vertically or horizontally. There is not a lot of time for troubleshooting or shaping if you want to make money.

At the time of his interview, John H. Guy III was considered one the best in the trade in Franklin County.

Rock fences are an integral part of Kentucky history, particularly in the Bluegrass region where the Shakers of Pleasant Hill lived for more than 100 years. The contributions of the skilled work of African American stonemasons is an important part of this history.

This blog is largely informed by the research of Dr. Karl Raitz and Carolyn Murray-Wooley. For more information on rock fences in the Bluegrass and the role of African Americans in this trade, please see the references listed below.

Bibliography

- “A Visit to the Shakers of Mercer Co. Ky.” Valley Farmer (October 1856).

- Carolyn Murray-Wooley and Karl Raitz, Stone Fences of the Bluegrass (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1992), 94.

- “History of Dry Stone Construction,” Dry Stone Conservancy. February 17, 2022. https://www.drystone.org/historyofdrystoneconstruction.

- Karl Raitz, email message to author, Feb 11, 2022.

- Karl Raitz, “Rock Fences and Preadaptation,” Geographical Review 85, no 1 (1995): 50-62.

- Pleasant Hill Shaker Village Church Record Book B, Covenant of 1844 Section II Institution of the Church, Harrodsburg Historical Society: 70.