Preserving and Interpreting Pleasant Hill

Maggie McAdams, Education and Engagement Manager

Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill is the largest National Historic Landmark in Kentucky with 34 original Shaker structures and 3,000 acres, but it took time and dedication to make it what it is today.

After Shakertown at Pleasant Hill, KY, Inc. was formed in 1961, the task before the organization was massive. The single purpose adopted by the original Board of Trustees was “to preserve the heritage of the Shakers and to promote an awareness on the part of the public of the historical significance of the Village of Pleasant Hill.”[1] They thus began the process of reassembling Pleasant Hill, one property at a time.

The buildings were in varying states of deterioration in the 1960s, so the first goal after acquisition was stabilization and preservation. The initial estimate to preserve and restore Shaker Village as a whole was $2,000,000, which today would come to $17,827,483. This sent a bit of a shock wave through the new organization. Though private support was, and still is, instrumental in ensuring the success of the site, the board successfully applied for an Area Redevelopment Act loan in 1963 to start the initial restoration work.

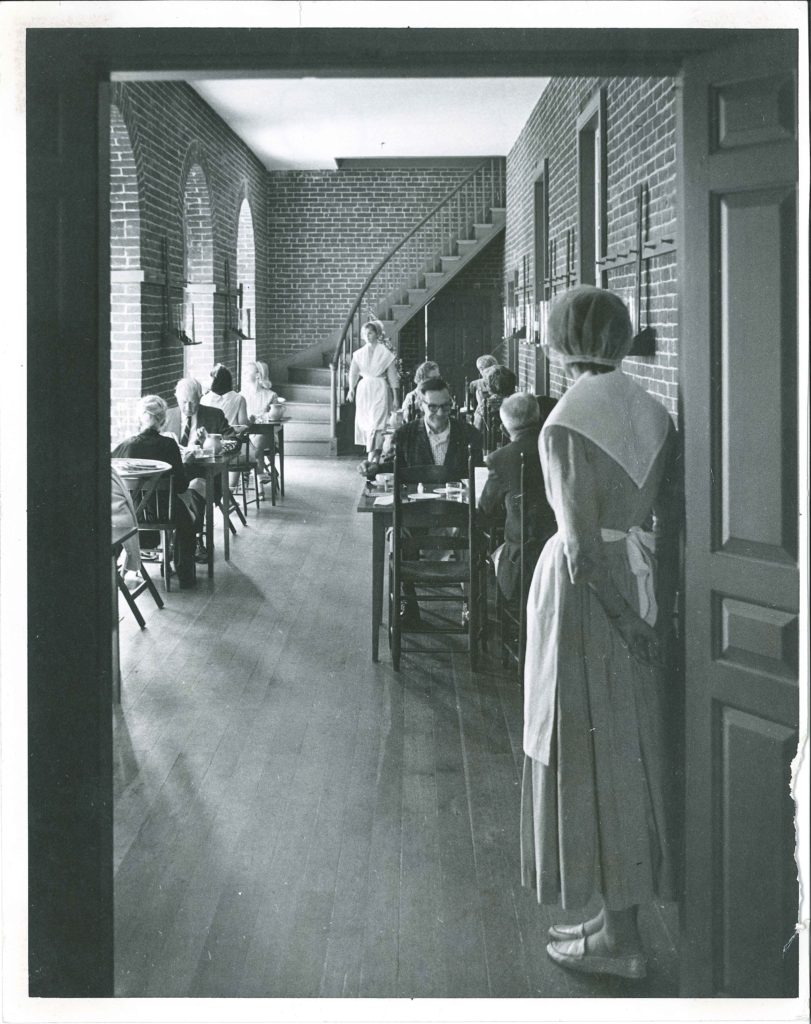

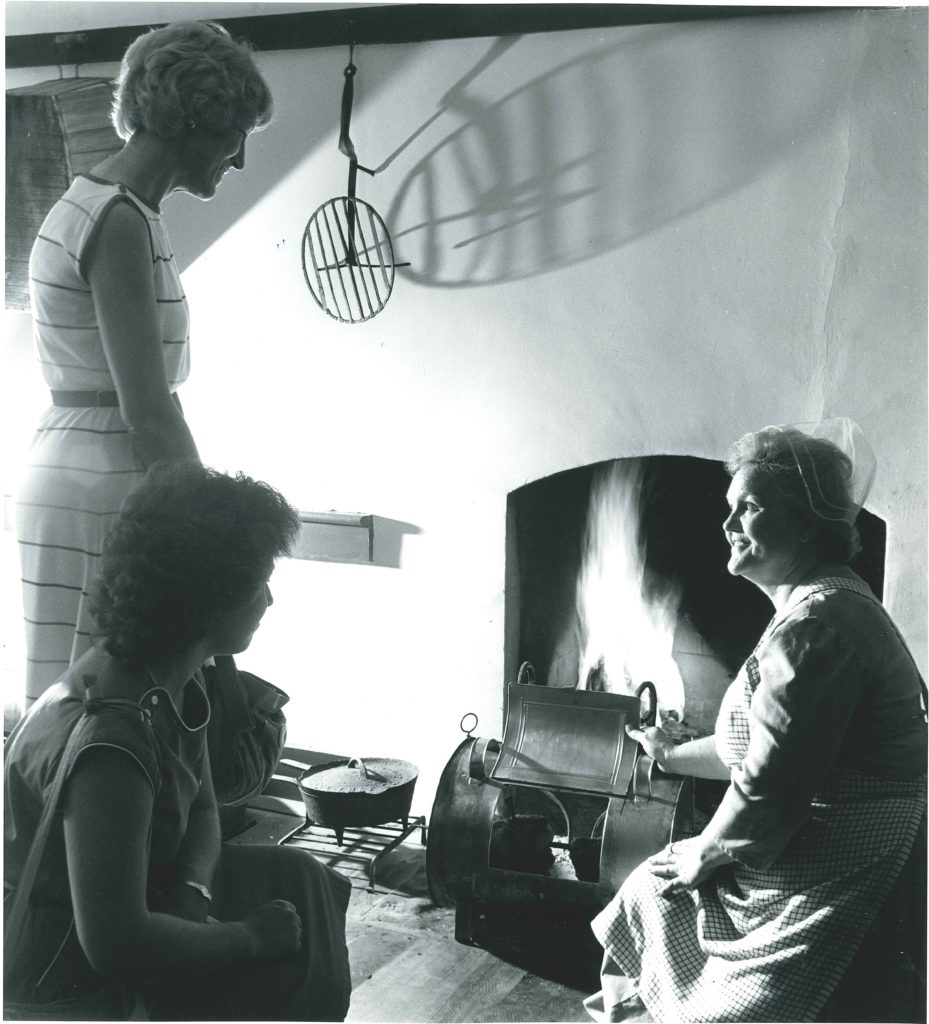

Earl Wallace and the board invited James Cogar, who had been the first curator at Colonial Williamsburg, to lead the restoration effort at Pleasant Hill. The organization chose to restore the buildings to the 1840s to capture a moment in time for this community, and followed an “adaptive reuse” preservation model. While building exteriors were being restored to the mid-19th century, some of the building interiors were being modified to accommodate overnight guests. This model meant that Shaker Village could continue to operate with earned revenue, and sometimes the best way to preserve a structure is to use it!

With only half of the buildings restored, Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill officially opened to the public on April 15, 1968. To tell the story of the Shakers in the 1840s, the organization employed the living history interpretive model in which interpreters, wearing period clothing, carried out tasks in order to set a scene of daily life in this community. The rise in popularity of living history sites coincided with the social history movement of the 1960s and 1970s in which scholars were focusing more on the lived experiences of the past. Social history sought to turn attention to the everyday experiences of people, and living history helped to answer this call in the public sector.

Today, Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill continues to explore the everyday lives of the Shakers, but in different ways. The past is stagnant and unchanging, history on the other hand is dynamic. History, as an interpretation of the past, is always changing as we uncover new evidence and find new ways to tell the stories of the past.

[1] Earl D. Wallace, A Review of the First Fifteen Years of Financing the Restoration of Pleasant Hill (KY: Shakertown at Pleasant Hill, KY Inc., 1975-1976), 4.