It takes a Village to save a Village.

Maggie McAdams, Education and Engagement Manager

After the last Pleasant Hill Shaker passed away in 1923, the once vast Shaker community ceased to exist as a religious society. The historic buildings that once formed the foundation for this community found new uses with new owners. Shakertown, as it was known locally, became another stop along Highway 68, with gas stations, general stores, restaurants and hotels interspersed among farms with houses and barns.

The First Attempt to Save Shakertown

There were very clear and deliberate efforts in the 1930s and 1940s to see Pleasant Hill set aside as a historic site or state park. Individuals and organizations were working on many fronts to see this happen. Burwell Marshall had purchased quite a bit of land during this period under the name Pleasant Hill Realty Co., and eventually opened a museum in the Centre Family Dwelling. It appeared that almost everyone with an interest in this village during this period, wanted to see it set aside and saved, and wanted to help interpret Shaker history by doing so.

By the 1950’s; however, momentum to save the site had waned. Though there were still interested parties, the buildings were in worse shape than ever with many on the brink of collapse.

The Renfrew Restaurant

By this time, the bulk of the original Shaker buildings were in the hands of just five individuals. The Gwinn brothers owned much of the West end of the Village, while Burwell Marshall retained ownership of the Centre and East portions. Robert and Bettye Renfrew purchased the Trustees’ Office in the 1950s to run a restaurant.

According to one of the restaurant regulars, “the place had a lot of character. It was like something out of a Faulkner novel, going there for dinner. It was a bring-your-own-bottle operation, and the food was wonderful. They just had a few things – a special eggplant casserole and fried chicken and old ham, but they’d never get it ready. Guests would sit out on the front steps and ‘kill a bottle of whiskey,’ and finally a member of the party would stroll back into the kitchen and casually ask, ‘How’re things coming, Mrs. Renfrew?’ The lady would look up at her interlocutor from her cup of tea, ‘but it wasn’t tea.’ Finally everybody would get fed, and then somebody would wind up the old Victrola in the corner and put on a record, and sometimes the waitress would join the dancing.”[1]

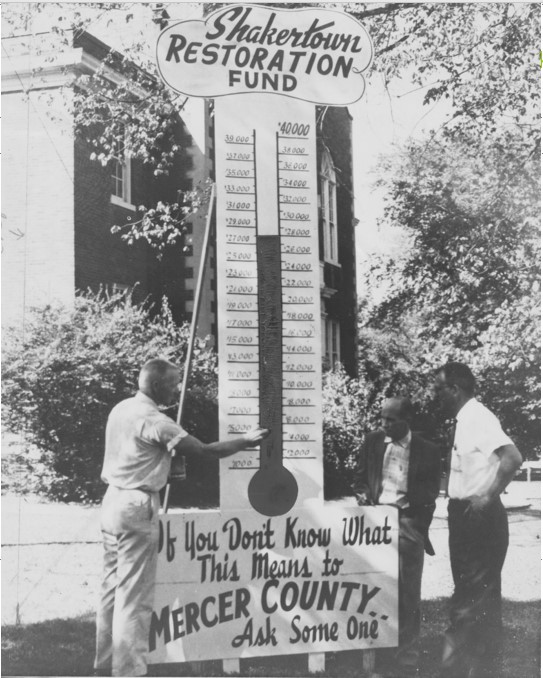

Raising Funds to Save Shakertown

Despite the charm of the buildings, it was apparent something drastic needed to be done. The effort to save Pleasant Hill was revived with the Shakertown Committee of the Bluegrass Trust for Historic Preservation. At a dinner in 1959 at the Shakertown Inn, the Renfrew’s restaurant, members of the Harrodsburg Historical Society, the Chamber of Commerce and other community leaders excitedly announced the formation of a committee to “explore methods to restore some fifteen buildings at Pleasant Hill and to make the place a historical and tourist site.”[2]

By 1962, the Shakertown Committee had secured options to be able to purchase many of the remaining Shaker buildings, but the combined figure of $362,000 was daunting! Earl Wallace, then chair of the board of Trustees, claimed “the first challenge to our enthusiasm came as the option on the present Trustees’ House was about to expire. We were faced with the payment of $62,500 which we did not have. The challenge came from Barry Bingham of Louisville who said that he would give $25,000 if we would raise the balance. The seriousness of our undertaking dawned on me and five other trustees when we had to endorse Shakertown’s note at a Lexington Bank to get the balance. I recall we said at that time that Shakertown would own one property if never another!”[3]

The Trustees’ Office was the first building purchased by the newly formed non-profit Shakertown at Pleasant Hill, Kentucky, Inc., and this decision was very deliberate; they viewed this building as the key to the restoration effort. This building was unanimously considered “the vital first purchase in the Shakertown project.”[4]

Preserving the Past for the Future

After subsequent waves of preservation and fundraising, the Village currently sits on 3,000 acres of Shaker land, which includes a nature preserve, farm and a historic site with 34 original Shaker structures remaining. Today, the Trustees’ Office continues to serve as an integral part of the Shaker Village experience. With shops, a restaurant, and guest rooms, this space allows visitors to connect with this historic site in a personal way.

Our mission at Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill is to inspire generations through discovery by sharing the legacies of the Kentucky Shakers. We do this by inviting the public to explore the Village, to stay the night and to take part in our daily programs that help interpret the Pleasant Hill story. We take the legacies of the Pleasant Hill Shakers to heart, and hope that these legacies continue to welcome visitors for years to come.

[1] Thomas Parrish, Restoring Shakertown: The Struggle to Save the Historic Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill (KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2005), 2.

[2] Ibid., 41-42.

[3] Earl D. Wallace, A Review of the First Fifteen Years of Financing the Restoration of Pleasant Hill (KY: Shakertown at Pleasant Hill, KY Inc., 1975-1976), 4.

[4] Parrish, Restoring Shakertown, 47-18.