Laura Webb, Program Specialist

Warning – The following post shares the stories of historic artifacts that have, in the past, “disappeared” from Shaker Village and returned in unusual ways. The management of Shaker Village would like our readers to know that we have excellent security and oversight of our artifacts!

Howdy, everyone! Welcome back to another installment of my dispatches from the SVPH archival digitization project.

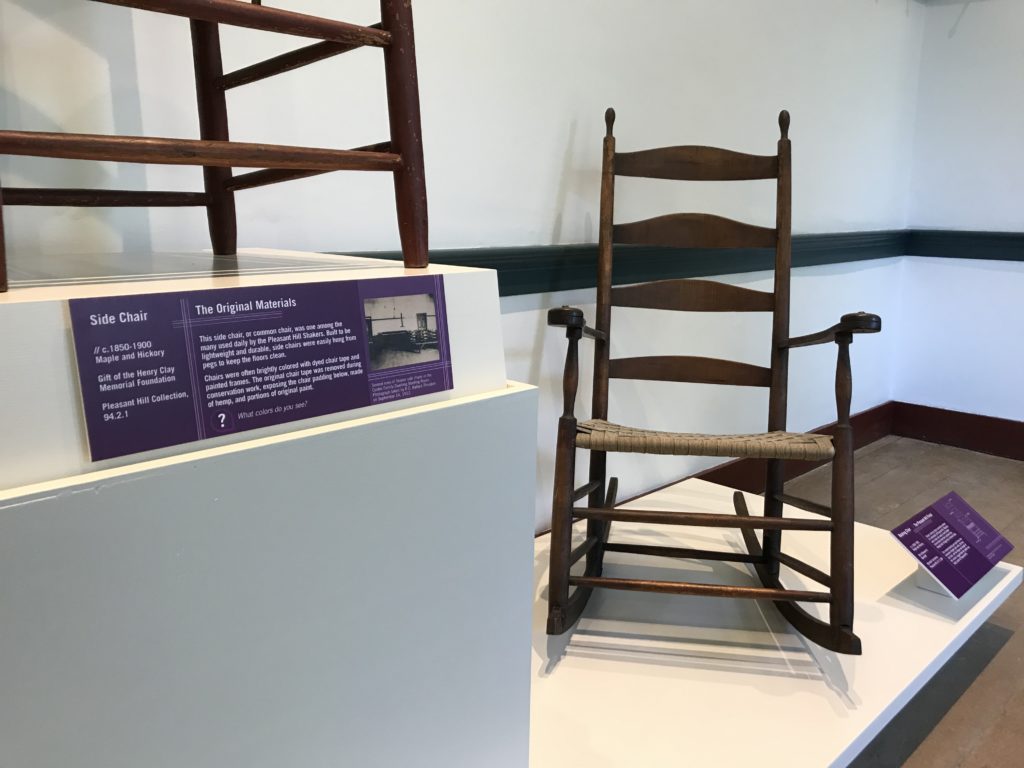

As many of you know, there is a lot of information we can glean from closely observing an object or artifact; but in most cases, this can’t tell us everything we want to know about it. That’s where our object files come in! When our digital catalog goes live, you will of course see photographs, descriptions, and measurements of the objects. You will also often see:

- Cross-references to related items (such as library holdings, archival documents, photographs, and even other objects),

- Examination notes by experts in a relevant field,

- Publications or exhibits that mentioned or featured the object, and/or

- Information that accompanied the object on its journey to our institution.

While checking over these entries, I have found many interesting and informative notes. I have also found several that are entertaining as all get-out. Guess what? Sometimes an object’s story doesn’t end at our threshold! So far, I’ve found at least two artifacts that have “wandered” a little further from home than they should have.

First is this basket (accession # 67.4.4), which first came to the village as a donation in 1967. Sometime in the 1970s-80s, it, ahem, “walked off.” This note explains how it found its way home in 2003:

“The sender had visited Pleasant Hill 12/18/2003 and told how she had ‘met a 92-year-old lady at a garage sale, who said a man who lived in her house for years; was in possession of this basket which apparently belongs to you—and she asked me if I’d return it to you.”

A roundabout journey, but effective! Of course, it begs the question of how the 92-year-old woman’s tenant acquired the basket in the first place, doesn’t it?

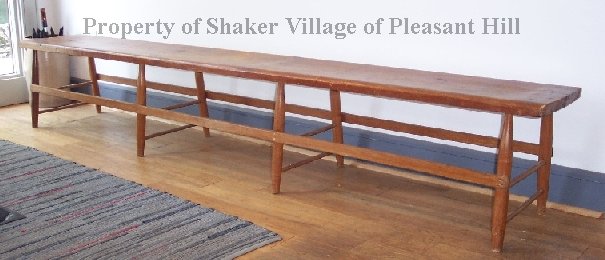

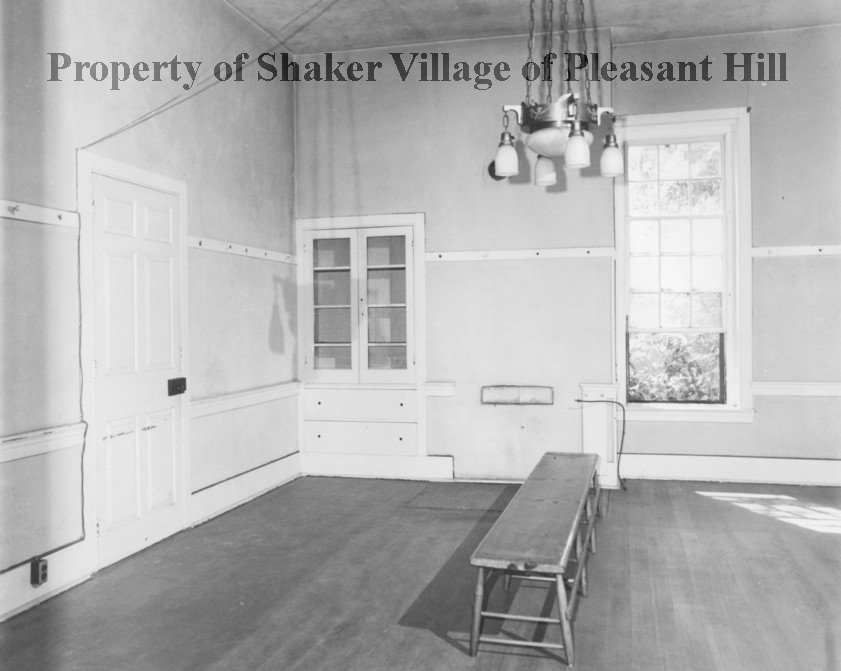

Second is this bench (accession # 61.4.386), which was part of the initial Pleasant Hill property purchase in 1961—meaning it’s been a fixture of our organization from the beginning. Pre-restoration photos show it living in the Trustee’s Office; post-restoration, it resided in the Carpenter’s Shop (currently our Welcome Center). However, in the mid-1970s, it…you guessed it, “walked off.”

On May 22nd, 2005, between 11:00 and 11:45 AM, it appeared in front of our administrative building with the following note:

“I am returning this to its rightful owner…It was taken by a former employee about 30 years ago. (NOT ME.) It eventually ended up in my possession. Now I give it back and pray that the “Curse” will cease on me and everyone associated with its removal from Shakertown. Thank you.”

For reference, please keep in mind that this bench is 8 ½ feet long. I have no idea how someone left the village with it unnoticed, but as they say, it was a different time. I also wonder what happened to make this person believe the bench was cursed.

Don’t try it at home, kids! I’m not saying a mysterious Shaker-themed curse will befall you if you steal from us, but I’m also not not saying that. Best not to risk it, right?

Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill was awarded a CARES grant through The National Endowment for the Humanities in June 2020. Funding from this grant award supported two activities to enhance digital humanities initiatives at SVPH, including Laura Webb’s work to review our collection records and prepare them for publishing in a public digital database.

Stories like this are being discovered here every day.

Stories like this are being discovered here every day.