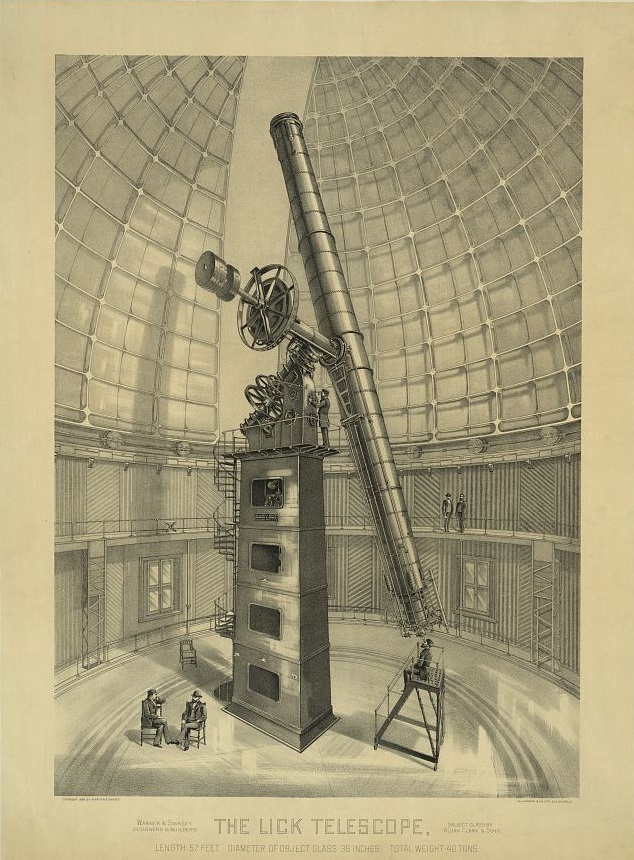

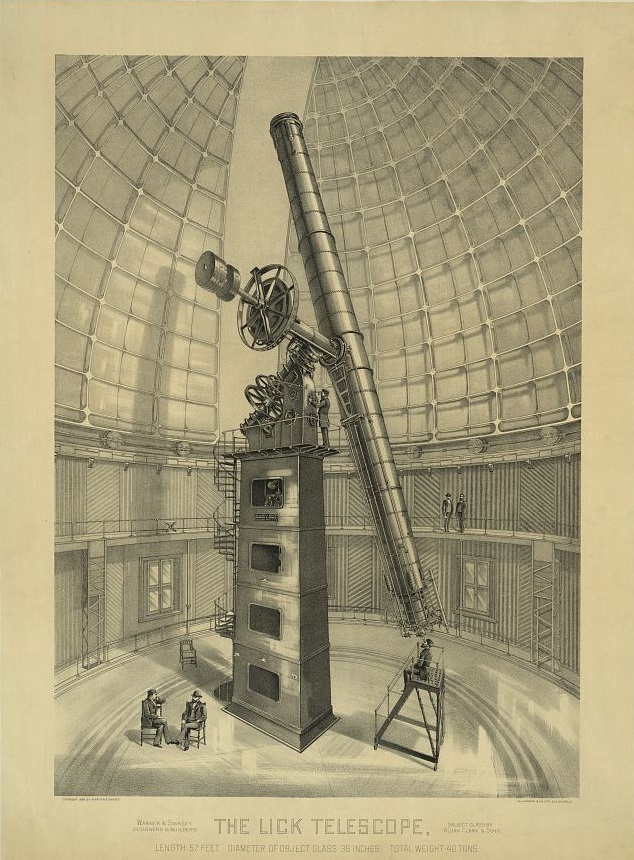

Lithograph of the Lick Observatory and telescope mentioned in a sermon printed in The Manifesto in 1891. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

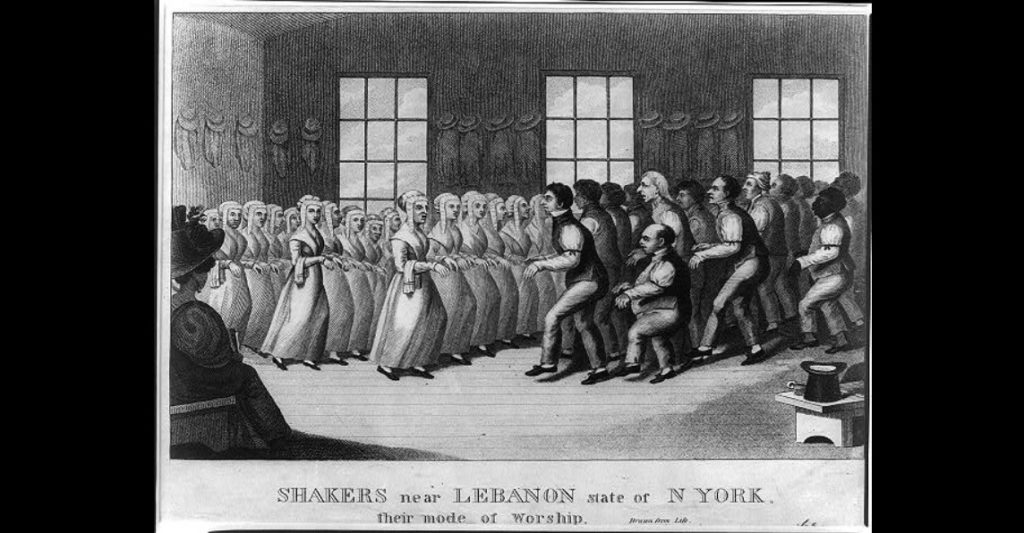

The Shakers were no strangers to celestial phenomena like the solar eclipse that will cast fleeting darkness over portions of states from South Carolina to Oregon—including Kentucky—on August 21. Their journals recount star patterns, moon phases, comet sightings, and solar and lunar eclipses. To some Shakers, the spectacles of space exemplified core principles of Shaker theology and culture like order, union and harmony; to others it was seen as nonsensical and foolish. Nonetheless, regardless of whether the majority of Shakers were supporters or skeptics of astronomy, records in the archives show cosmological rhetoric made its way into their schools, journals, eulogies, poetry and farming practices.

SHAKER STARGAZERS

Unable to ignore the many astronomical wonders of the night sky, the Pleasant Hill Shakers recorded sightings of cosmic marvels ranging from eclipses and comets to moon irregularities. In each instance, they noted specific details about the time of day, duration, totality and any remarkable characteristics of the astronomical occurrences they observed:

- March 19, 1843 At this time there is a comet to be seen which appeared about a week ago. It has an extraordinary long tail stretching nearly halfway across the hemisphere toward the south though not very brilliant (sic). It appears to be a stranger to astronomers.

- March 25, 1857 The sun was eclipsed this eve. visable only for 8 or 10 minutes.

- December 6, 1862 Last night we had a total eclipse of the moon.

- August 7, 1869 At ½ past five o’clock in the evening the sun was total eclipsed.

- June 24, 1881 There is a large comet now to be seen in the N.E. [non periodic comet] We see it best at 3 in the morning than any other time.

- October 4, 1882 A Comet is to be Seen at this time in an easterly direction. East South East. between 4 & 5 oclock A.M. among the longest & most brilliant ever Yet Seen A beautiful Sight!

- February 24, 1897 The moons of Feb & March have laid on their backs and it has rained nearly the whole time in these two months.

- May 28, 1900 Sun in eclipse from 6:30 to 8:30 A.M. about 9/10 totality.

In 1866 and 1867, the Pleasant Hill Shakers recorded seeing a “big circle” and “bright circle” around the moon—an optical phenomenon called a lunar halo in which light cast onto the moon’s surface by the sun refracts through ice crystals in Earth’s atmosphere, resulting in an eerie ring.

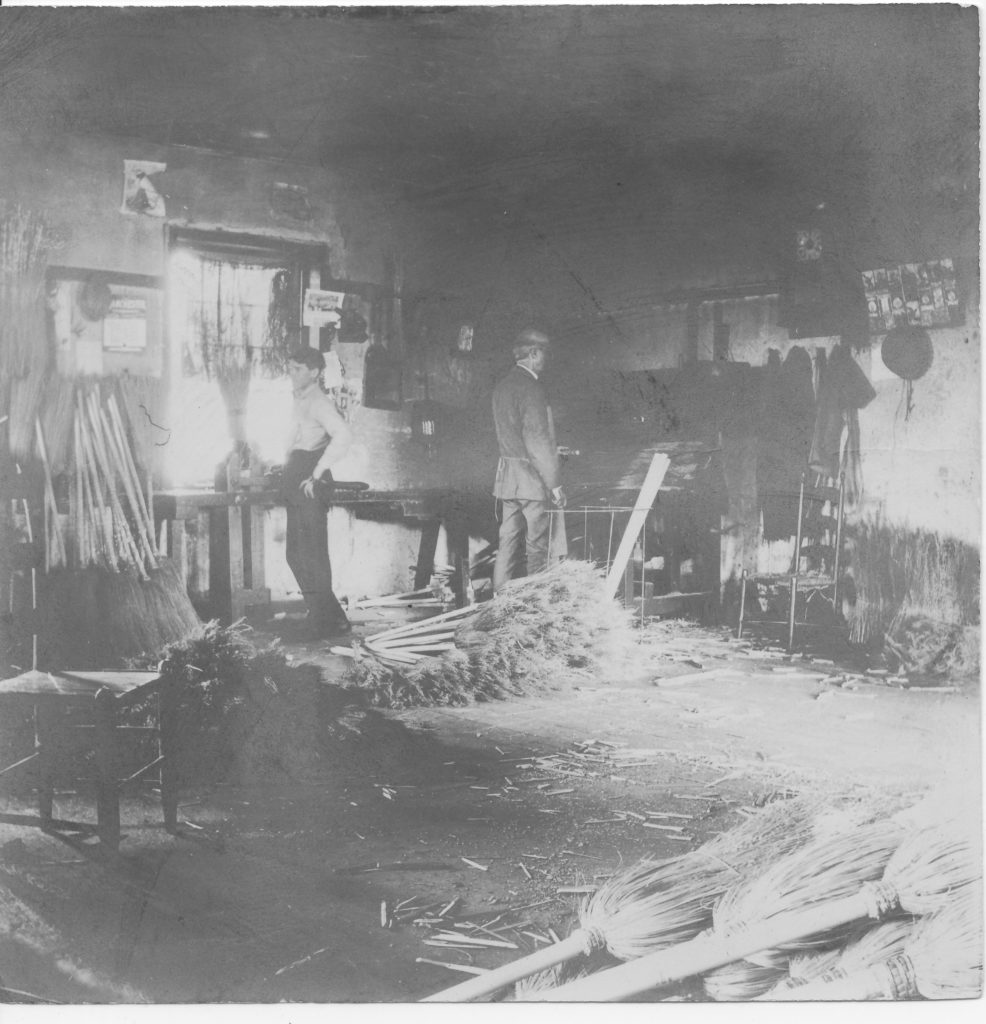

ASTRONOMY + SHAKER AGRICULTURE

The Shakers were very much in-tune with natural and celestial cycles and used their knowledge of astronomy—and, in some cases, astrology—to inform their agricultural practices. In a report written on behalf of the Mount Lebanon Shakers in July 1898, Calvin G. Reed tells how, at the recommendation of astronomers, the community had taken up a “free journey on the earth’s stupendous railway,” during which they observed six signs of the zodiac, including Leo. While they found “the Lion’s breath rather too hot for unalloyed comfort” in July, by September, the Shakers record a change in the seasons and agricultural schedule in a direct correlation to the stars, explaining, “this is the harvest season of the year as the constellation Libra or the Scales denotes, the season of gathering in the fruits of the earth.”[i]

Though not always pleased with the results, the Pleasant Hill Shakers placed a degree of confidence in the authority of almanacs, from which they gleaned weather forecasts, planting charts, tide tables and astronomical informational upon which to base their agricultural decisions. In August 1857, one journal keeper reflected upon the Almanac’s predictions of rain during the last quarter of the moon, troubled that if it rained as much as the publication claimed it would, based upon the moon phase, it would be “almost impossible” for them to thrash their grain.[ii]

ASTRONOMY + SHAKER SKEPTICS

While many Shakers found astronomy relevant in the realms of education, creative writing and farm work, not everyone was persuaded. Maintaining the belief that astral bodies had no effect on what happened on the earth below, some Pleasant Hill Shakers—particularly farmers—were adamant critics, filling journal pages with ridicule at any notion suggesting agriculturalists should put their trust in astronomical or astrological events. Particularly skeptical, farmer and journal keeper James Levi Ballance sized-up the influences of the moon on the Earth in these ways:

“…it is very inconsistent to imagine the moon has any influence over the weather….The moon must be very smart to make it rain or snow here and at the same time not suffer it to rain or snow there. The tides are also partial and local and of course they are not under the influence of the moon.”[i]

“Common sense and stubborn facts should have done away with the moon making it rain many years ago.”[ii]

“It did not rain at our farm 4 miles above us, there was a little sprinkle and here we were thoroughly saturated with water, they must have had a different moon from ours or else there is no truth in the moon making it rain (all a humbug).”[iii]

ASTRONOMY + SHAKER VILLAGE TODAY

The archival records at Shaker Village indicate the Shakers were just as intrigued by the wonders of space as modern spectators are today. Join us this winter at Shaker Village for a guided stargazing experience as part of our special $5 after 5pm series in January and February!

Plan you astronomical adventures in 2020 at Shaker Village with special programs led by the Bluegrass Amateur Astronomy Club, guided night hikes led by Shaker Village staff, and moonlight paddles along the Kentucky River!”

[i] “Notes about Home,” Calvin G. Reed, The Manifesto, Vol. 28, No. 11, November 1898

[ii] Journal, April 1, 1854-March 31, 1860, Bohon Shaker Collection, Volume 11, Filson Historical Society

[i] Journal, April 1, 1860-December 31, 1866, Bohon Shaker Collection, Volume 12, Filson Historical Society

[ii] Journal, November 23, 1871-July 31, 1880, Bohon Shaker Collection, Volume 14, Filson Historical Society

[iii] Journal, April 1, 1860-December 31, 1866, Bohon Shaker Collection, Volume 12, Filson Historical Society

Historical content originally researched and written by Emalee Krulish in 2017.