Jacob Glover, Ph.D., Director of Public Programs and Education

“Great architecture has this capacity to adapt to changing functional uses without losing one bit of its dignity or one bit of its original intention.

– Thomas Krens, former Director of the Guggenheim

As we approach the end of October and the 200th anniversary of the Pleasant Hill Meeting House, we have taken the opportunity to reflect on the both the history of the Meeting House and its continuing legacy and influence here at Shaker Village. As the quote that opens this blog post implies, the Meeting House has been remarkably resilient throughout the course of its existence and its many alterations since 1820.

When thinking about the original intention of the Meeting House for the Shakers at Pleasant Hill, it is important to keep in mind how the space was purpose-built to allow certain aspects of Shaker society to flourish. For the Shakers, the Meeting House was always about things such as unity, community, and faith. Of course, the Shakers’ religious beliefs influenced all aspects of their life, but the common worship area of the Meeting House was an extremely important physical space where the Shakers could gather on a weekly basis and reinforce communal ties, a shared sense of belonging, and strengthen their union with one another.

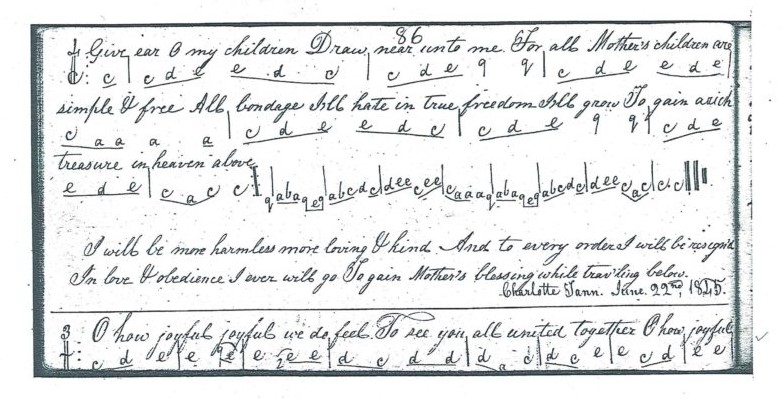

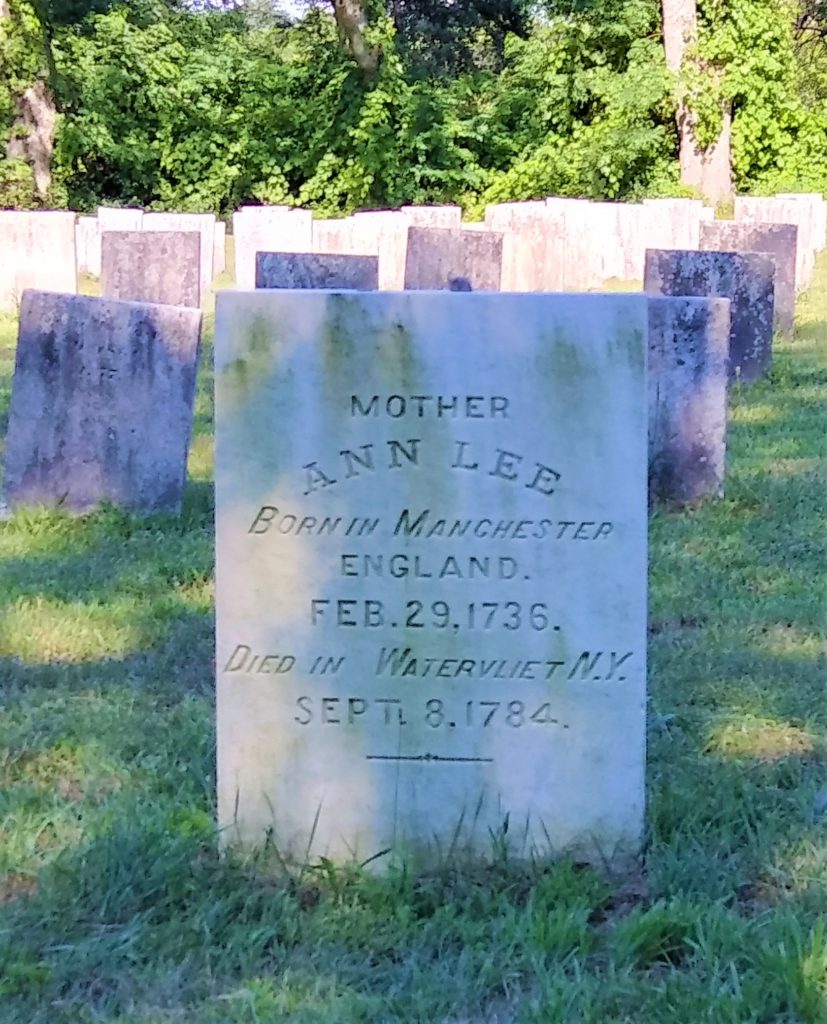

Given the important of these notions to the entire Shaker worldview, it is no wonder that the Meeting House held such a place of prominence in every community. When Shaker brothers and sisters danced and sang with each other, they cemented bonds that not only held together the community at Pleasant Hill — these actions provided a shared identity for Shakers all across America who danced the same dances and sang the same songs in similar buildings from Maine to Ohio.

At Shaker Village today, the Meeting House retains much of its original charm and capacity to inspire, even if the form and shape of that inspiration holds different meanings for us than it did for the Shakers. The sense of belonging and togetherness that was so important to the Shakers remains present in our daily Shaker music programs and special events like the Community Sing and Illuminated Evenings, as building community through song is still as strong an influence as ever.

The solidity and permanence of the Meeting House is also reminder of the power of place in a modern world that seems to become more transient and transparent by the day. Walking in the attic, the massive king posts and trusses are reminders of the ancient forests of central Kentucky and the long years that the oak trees graced the Bluegrass before they were hewed by the Shakers to build such a lasting testament to their architectural skills and their faith.

At Pleasant Hill, we remain as committed as ever to inspiring our local communities and state by sharing the legacies of the Kentucky Shakers, and the Meeting House will continue to be an integral part of that mission for our organization.

Join us at Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill on Saturday, October 31, 2020, for the 200th Anniversary celebration of the Meeting House. Special tours of the Meeting House focusing on Shaker song, dance and the building’s architecture will be available with purchase of admission.