Maggie McAdams, Assistant Program Manager

This blog post is dedicated to Rebekah Roberts who sought the truth in the past, and tried to give voice to the voiceless.

In 1899, visitors from Berea arrived at Pleasant Hill for a meal. As they began eating, they asked the Shaker “sister in charge” a series of questions to learn more about the history and beliefs of the Shakers.

“‘How do you deal with such difficult problems as woman’s rights?’

Jane Sutton, the sister in charge, responded:

‘Theoretically the brethren and sisters are equal in all things, but practically,’ with a little laugh, ‘the brethren try to keep just a little ahead.'” (The Berea Reporter, “Shakertown,” April 3, 1899)

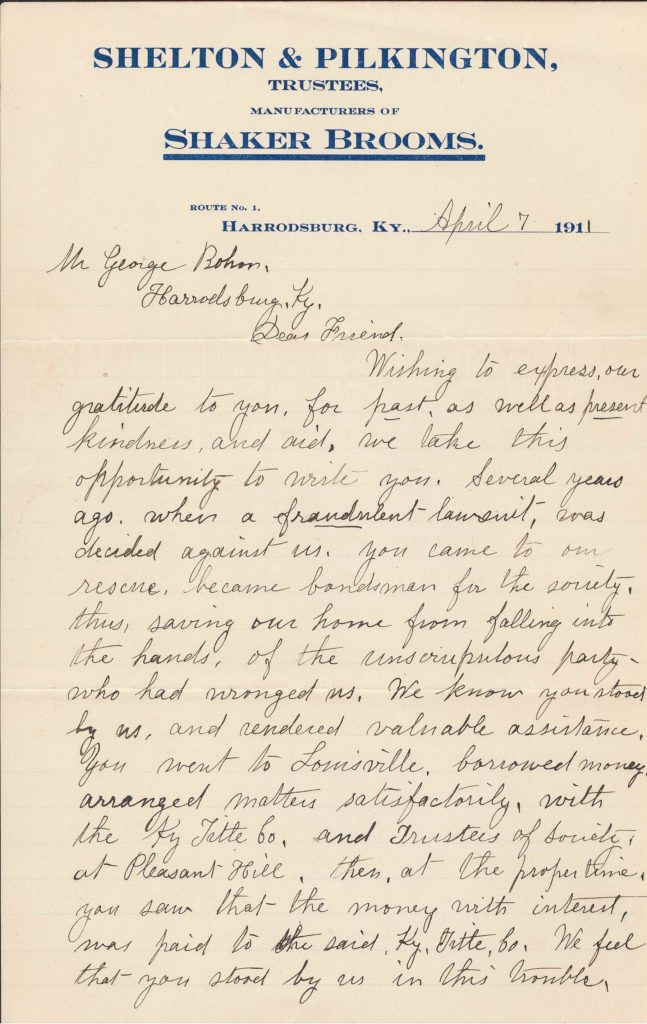

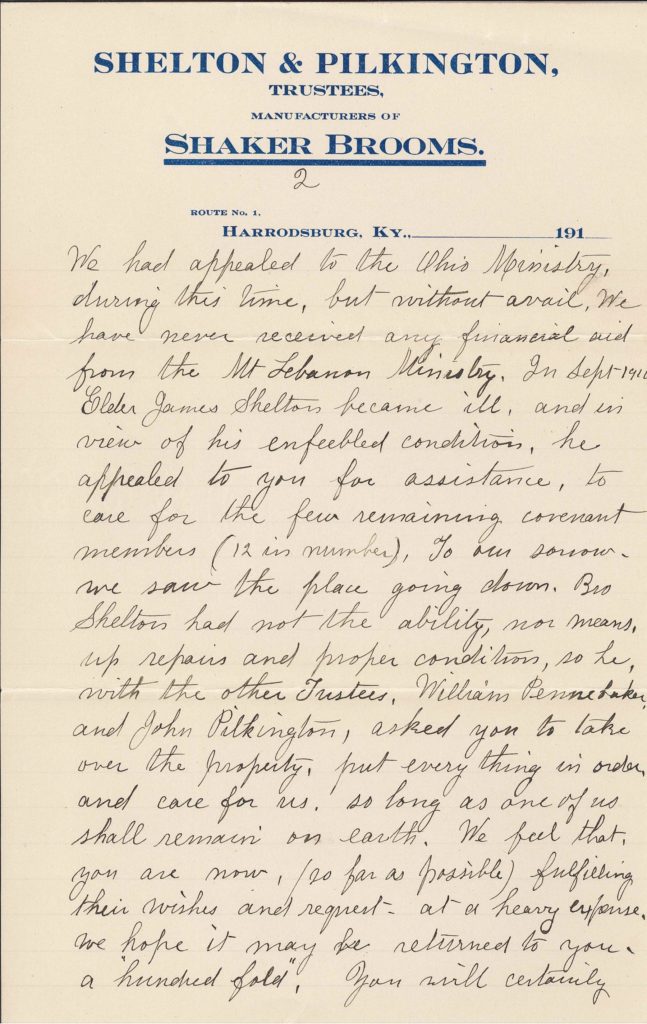

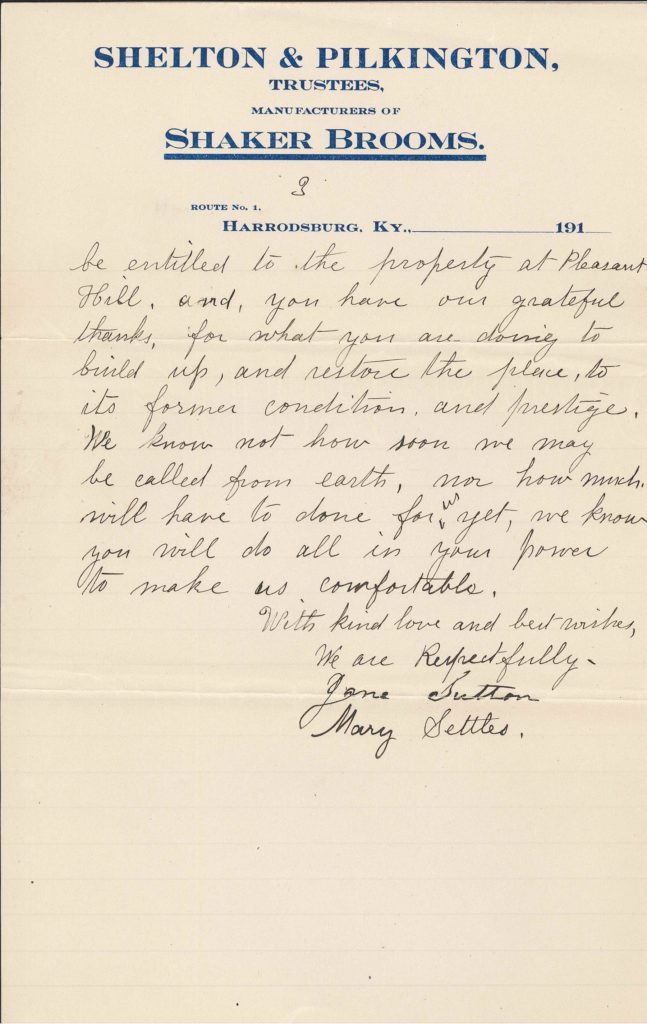

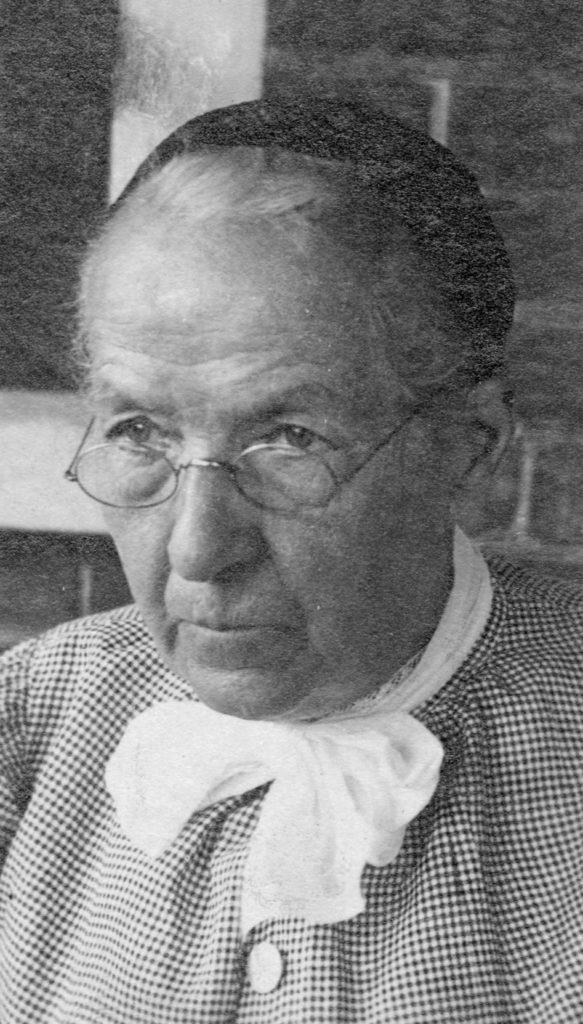

As a woman in power at Pleasant Hill, Jane Sutton would know! Pleasant Hill’s first and only active female Trustee, Jane Sutton saw the practical reality of doing business as a woman in the 19th century.

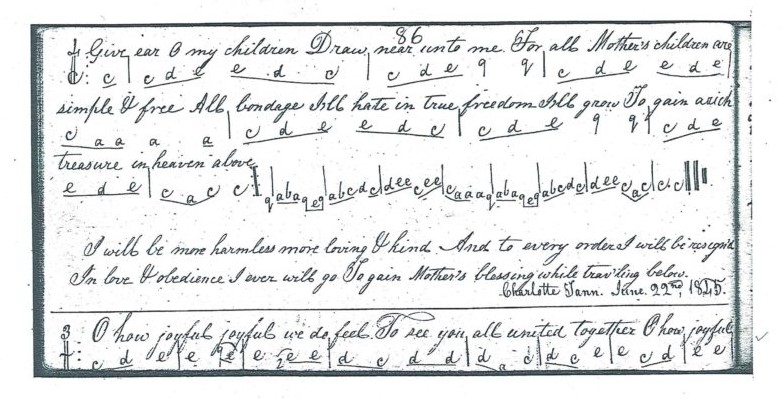

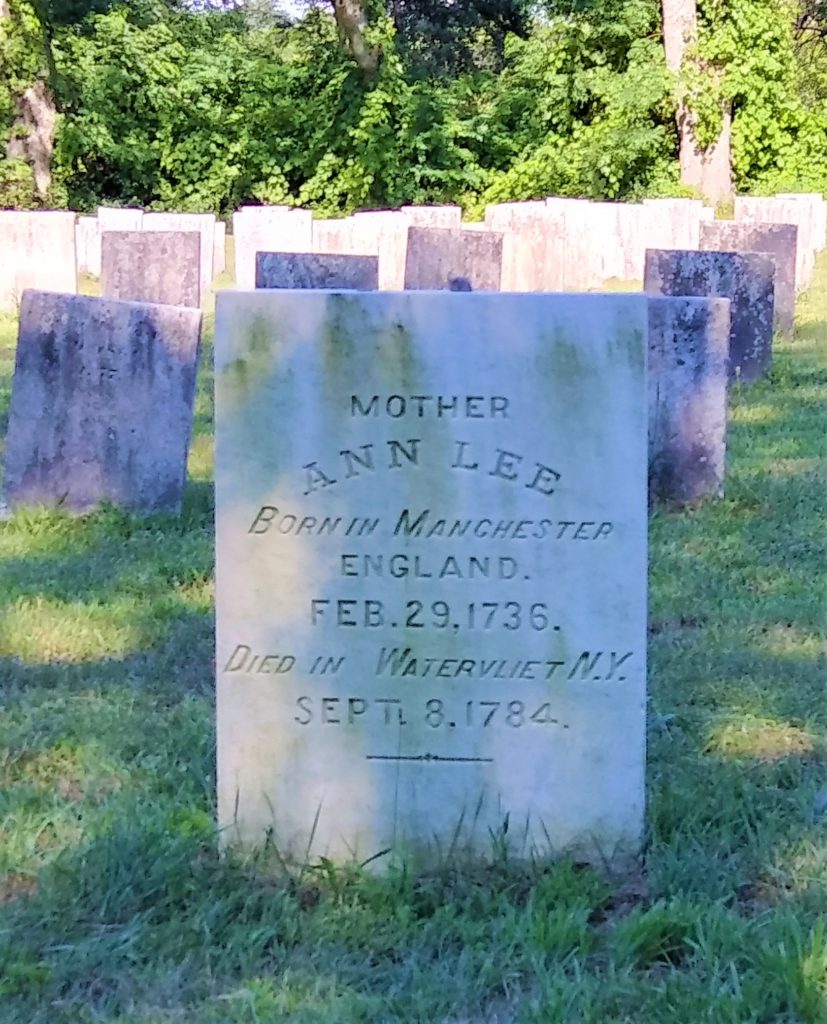

Gender equality has always been a core belief of the Shaker faith. Men and women were equal in all things through the Shaker’s belief in the duality of God. This belief was manifested in the leadership and hierarchical structure of Shaker communities. Gender equality in practice for the Shakers meant that all received an education, all could aspire to leadership roles, and all had access to the same accommodations and amenities. Yet, the Shakers were still products of the 19th century.

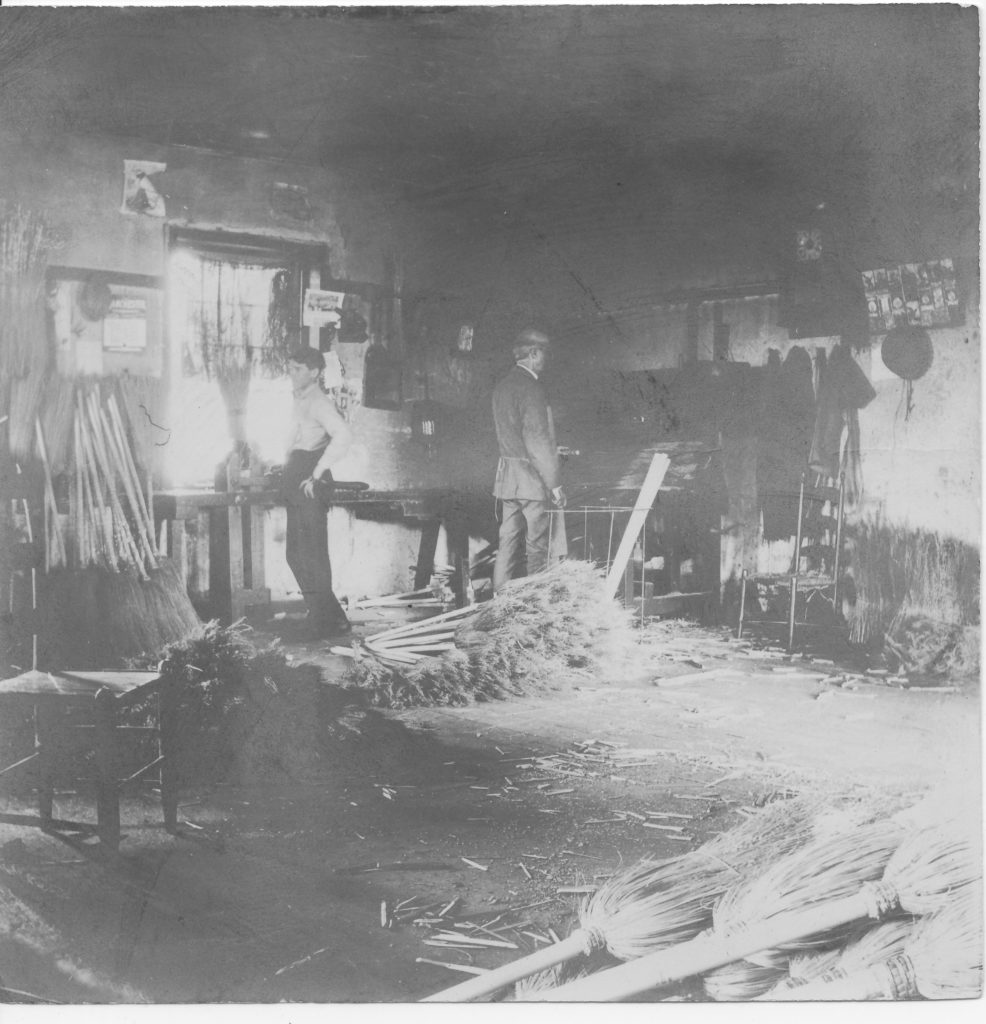

During the 19th century, men and women were thought to inhabit separate spheres in society, with women inhabiting the private sphere and men the public sphere. Often referred to as the ‘Cult of Domesticity,’ it was believed that woman, as traditional caregivers, had control of the home, the children, and domestic affairs. This gendered role also dictated that women had no place in the business world that existed outside of the home. Though the Shakers practiced gender equality in their leadership structure, these traditional gender roles were still present in their distribution of labor. Shaker sisters were responsible for cleaning, cooking, laundry, and textile production, while Shaker brethren were responsible for broom production, furniture making, tending to the livestock and crops, and other matters of industry.

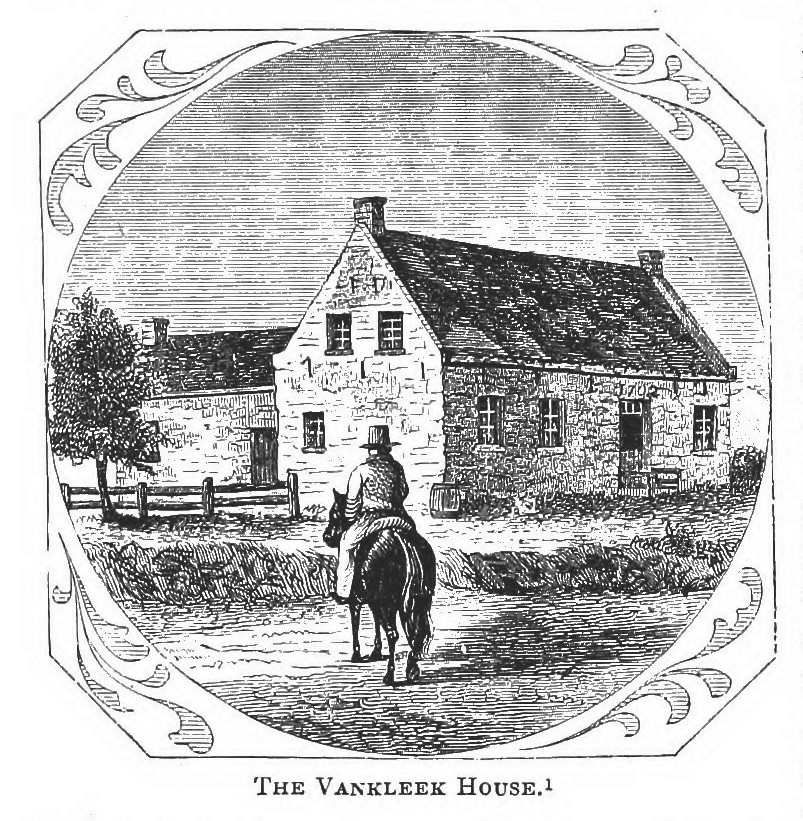

Men and women did have equal say in matters of governance at Pleasant Hill, but women did not have access to leadership in business for much of the 19th century. Throughout the history of Pleasant Hill, there were usually two male Trustees that handled the community’s finances, legal deeds and contracts, and managed commercial partnerships with businesses of the world. Women did have a role at the Office, but their primary responsibility was to cook and clean, and serve meals to the visiting public.

As demographics shifted in the second half of the 1800s, however, women began to assume more responsibility based on need. Sister Jane Sutton was one such woman.

Village’s Office.

Sister Jane Sutton was born in 1832, and arrived at Pleasant Hill in 1834. By 1868 she went to live and work in the Office. Journal records indicate that Sutton joined Pleasant Hill Trustees on trading trips throughout the 1870s and 1880s, and oversaw the “public dining room” at the Trustees’ Office. On Oct. 1, 1894, she was officially appointed a Trustee along with two other Shakers. In her role as Trustee, she also oversaw the Shaker Hotel after it opened in 1897 to visitors. By 1910, however, it appears that Sutton no longer served as a Trustee. In the contract that sold the declining community’s lands to a local businessman, Sister Jane was not listed as one of the official Trustees that signed their names to the contract. Though she and her fellow sisters outnumbered the remaining men of the community, 10 to 2 in fact, the men took charge of this final matter of business.

Sister Jane Sutton passed away on December 29, 1912. The following journal entry was written in the weeks before her passing, “Sister Jane is known and loved by everyone. She has been one of the commanding figures of Shakertown for years and is a natural leader who would command respect and a following no matter in what walk of life she had been placed. There are many, even outside the Shaker Village, who will grieve that her firm hand is beginning to tremble with the weakness of age.”

While gender equality was a staple of Shaker ideology, it appears in practice that such equity was often hard to obtain. Jane Sutton provides us with a glimpse into the world of nineteenth century business from the female point of view, and as she says, with a little laugh, “the brethren try to keep just a little ahead.”