Maggie McAdams, Assistant Program Manager

“’Tis a gift to be simple, ‘tis a gift to be free, ‘tis a gift to come down where you ought to be…”

Simplicity has become synonymous with the Shaker experience – as has the song Simple Gifts, emphasis on simple. The most obvious visible manifestation of the Shaker legacy of simplicity can be seen today in the form and function of their architecture and furniture, but in reality this value infused all aspects of the Shaker’s life. What we see, however, was far from simple to achieve.

Today, the word simple has come to mean plain or easily done, basic or uncomplicated, but for the Shakers, it meant something so much more.

The Shakers considered simplicity to be a sacred gift, one that members worked their entire lives to achieve. Simplicity to the shakers meant modesty and humility, and was a constant reminder to focus on faith and their spiritual path.

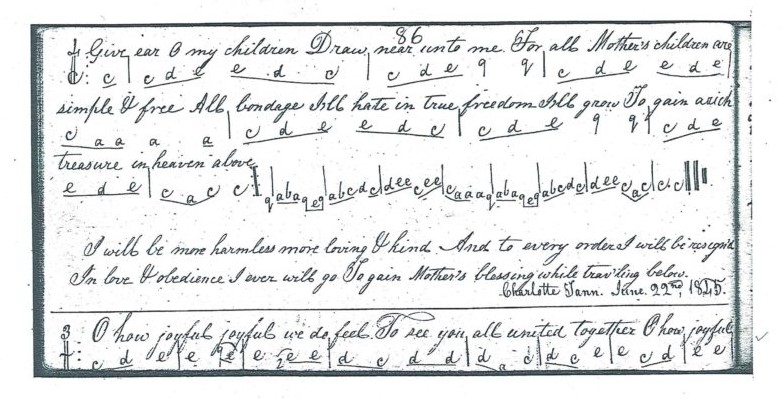

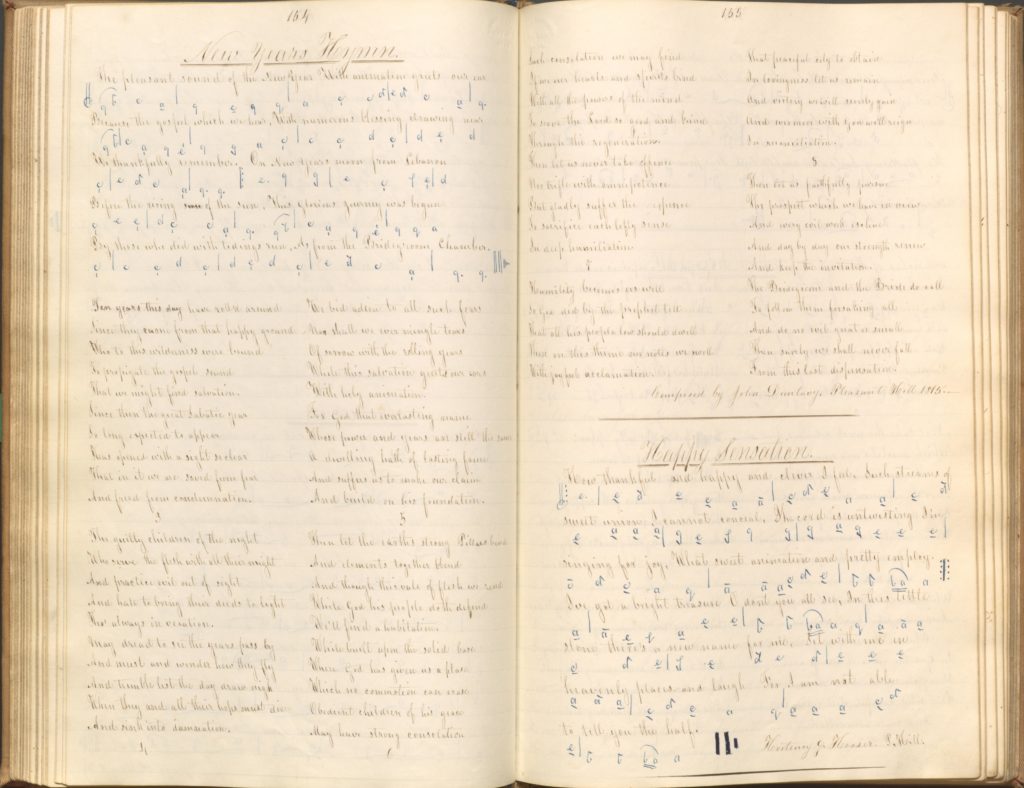

In music written for Shaker worship, simplicity is often portrayed as a willow tree, humbly bowing, and bending, and being open to accept God’s gifts.

“I will bow and be simple, I will bow and be free, I will bow and be humble, yea, bow like the willow tree.”

Themes of simplicity can also be found in the Millennial Laws, the rules that the Shakers lived by. Upon entering the Pleasant Hill community, members deeded their personal possessions to the society, and were given modest goods and attire to meet their basic needs.

All members lived communally and supported one another. To live simply meant to shed all excess and focus on the inward path of the soul, rather than on pride and vanity and material goods.

Hand labor was thought to be good for the soul, and craftsmanship in this way became a symbol for moving closer to God. “Put your hands to work, and your hearts to God.”

Pleasant Hill, KY.

To create a perfect piece of furniture was not an aesthetic pursuit, but a spiritual one. Craftsmanship was not perfected for personal gain or glory, and the difficult process helped to teach members humility. The Millennial Laws reiterated this by prohibiting signatures and unnecessary markings on items of manufacture so that the end product would not distract from the process and utility of the piece.

The Shakers wasted no design detail, and even their structures were built based upon functionality. As a result they appear quite simple. The peg lined walls, the large built-in cupboards, and the spacious floors of the dwelling houses – it took thoughtful design to create such orderly and simple spaces.

At Pleasant Hill, the dual spiral staircase in the Trustees’ Office is the perfect juxtaposition between the simple and the complex, as what appears to flow upward with such ease hides the intricacy that lies just beneath the surface.

Accessible through a stairwell door, the heavy structure that supports the staircase is an impressive work of engineering. The technical elements (like the massive timbers and the cantilevered steps), however, are concealed in favor of the simple and graceful free flowing aesthetic. What we are left with in the upward movement of the staircase is the embodiment of simplicity, of elevating the spirit toward the light.

The next time you see the Trustees’ Office staircase, or a piece of Shaker furniture, or you hum the tune to Simple Gifts, or you hear the lines ”When true simplicity is gained,” remember that true simplicity was hard to achieve – but that’s what made it so worth striving toward.

Simplicity is a gift.