Holly Wood, Music Program Specialist

“And I am thankful I was called into the gospel when I was a child, and I am also thankful I can say, that I never turned my back on the way of God although I have had some very trying scenes of trouble and distress to pass through . . .” {1} – Sister Charlotte Tann at Pleasant Hill, Kentucky, 1841.

Here are a few examples of those “trying scenes”:

- Living in the chaos of the 1811 New Madrid earthquake on the Western frontier, where aftershocks disrupted the isolated community for months.

- The War of 1812 caused thirteen year old Charlotte Tann to flee from West Union Shaker Village with hundreds of pacifist Shakers on a 431 mile journey to safety.

- Returning home after two years of war to discover her entire village destroyed.

- Orphaned at age fifteen.

- The closing of her childhood Shaker community and removal to Pleasant Hill, Kentucky.

When the Indiana community formally closed, Charlotte Tann was assigned by the Shaker ministry to live as a free person of color in Kentucky, a slave owning state.

How did this woman of faith, this unsung pioneer, face the difficulties of her life?

Tann’s testimony reflects the perseverance of a woman who’s trying life did not break her. She survived loss, disease, war and grappled with societal inequities while staying devoted and strengthened by the faith.

“And now I will give myself up to Mother and her good work, and labor to gather in a substance and treasure up the gospel into my own soul, for it is my unshaken faith and resolution to abide and endure to the end, let what will come.” {2}

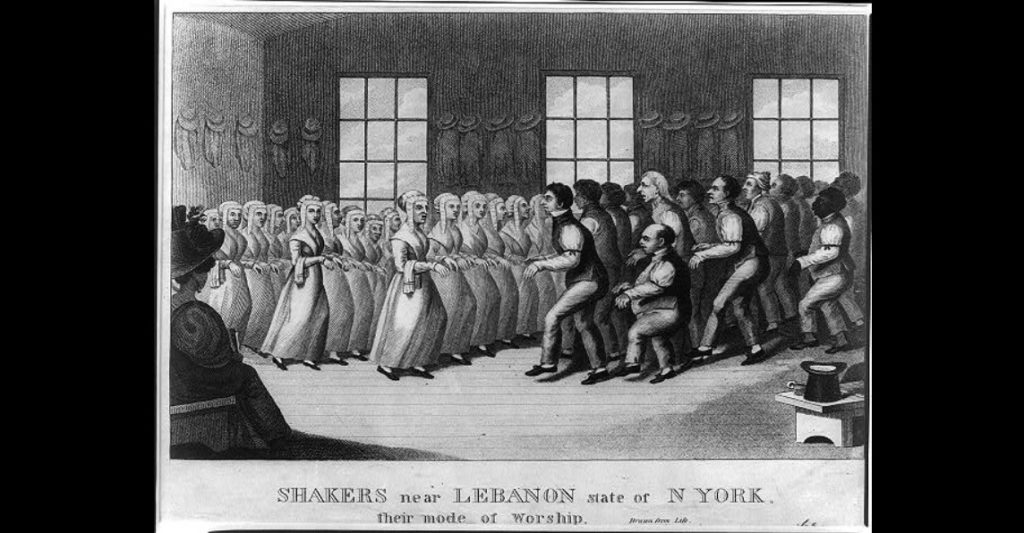

Her faith compelled her to heal and to flourish. As believers in gender equality, the Shakers recognized the spiritual gifts of both women and men. Pleasant Hill had a wealth of women who wrote beautiful Shaker hymns and, unlike so many women in the world, the Shaker women were recognized as the composers.

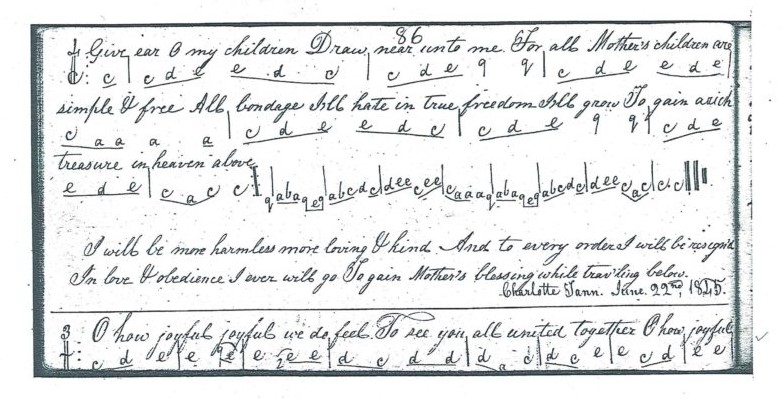

Sister Charlotte was referred to as an “inspired instrument,” or, led by God to compose. She wrote many songs, including “Give Ear O My Children,” which admonishes all bondage and hails freedom, love and kindness as the tools to gain entry to Mother’s heaven above.

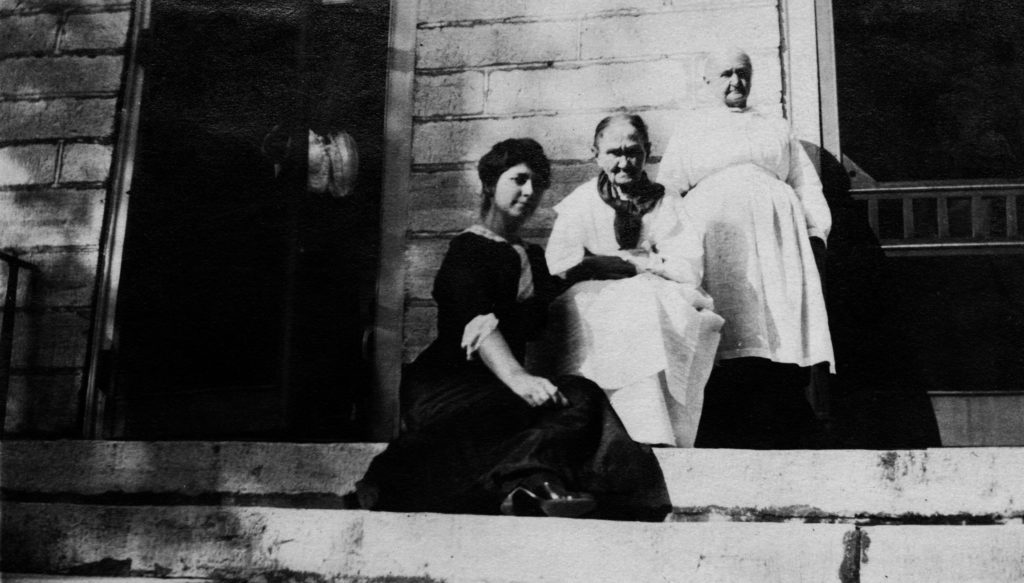

Upon the passing of this resilient woman in 1875, the Pleasant Hill Shakers reflected on her as a tower of faith:

“And thus has fallen another Veteran that has stood since childhood through many trying scenes . . . She is worthy of much honor, for She has been a faithful and zealous Surporter of the cause.” {3}

Learn more about Sister Charlotte Tann, and the stories of other Shakers from Pleasant Hill, on tours conducted daily at Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill.

{1} Testimony of Charlotte Tann, “Testimonies of the Pleasant Hill Shakers,” WR-VI-B49 pp. 38-40

{2} Ibid

{3} Filson Club: Bohon Shaker Collection. Volume 16 of 40 volumes.

A Ministerial Journal. October 24, 1868 – September 30, 1880. March 15, 1875. Page 140.