Jacob Glover, PhD. Program Manager

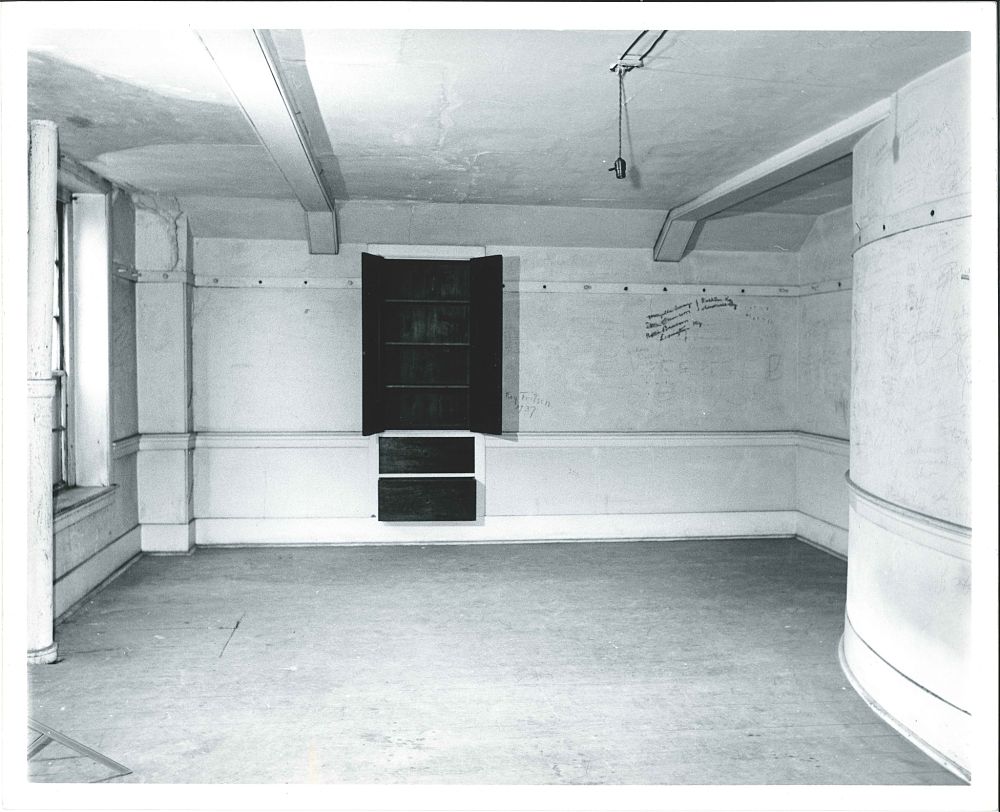

“…We visited the department for the sick which was under the charge of Jane Ryan.…The infirmary is in the dwelling house & adjoining the meeting room.” – Henry C. Blinn, “A Journey to Kentucky in the Year 1873”

Henry Blinn’s description of the infirmary in the Centre Family Dwelling at Pleasant Hill is a reminder of some of the unique healthcare challenges (and opportunities) that confronted the Shakers in nineteenth century America.

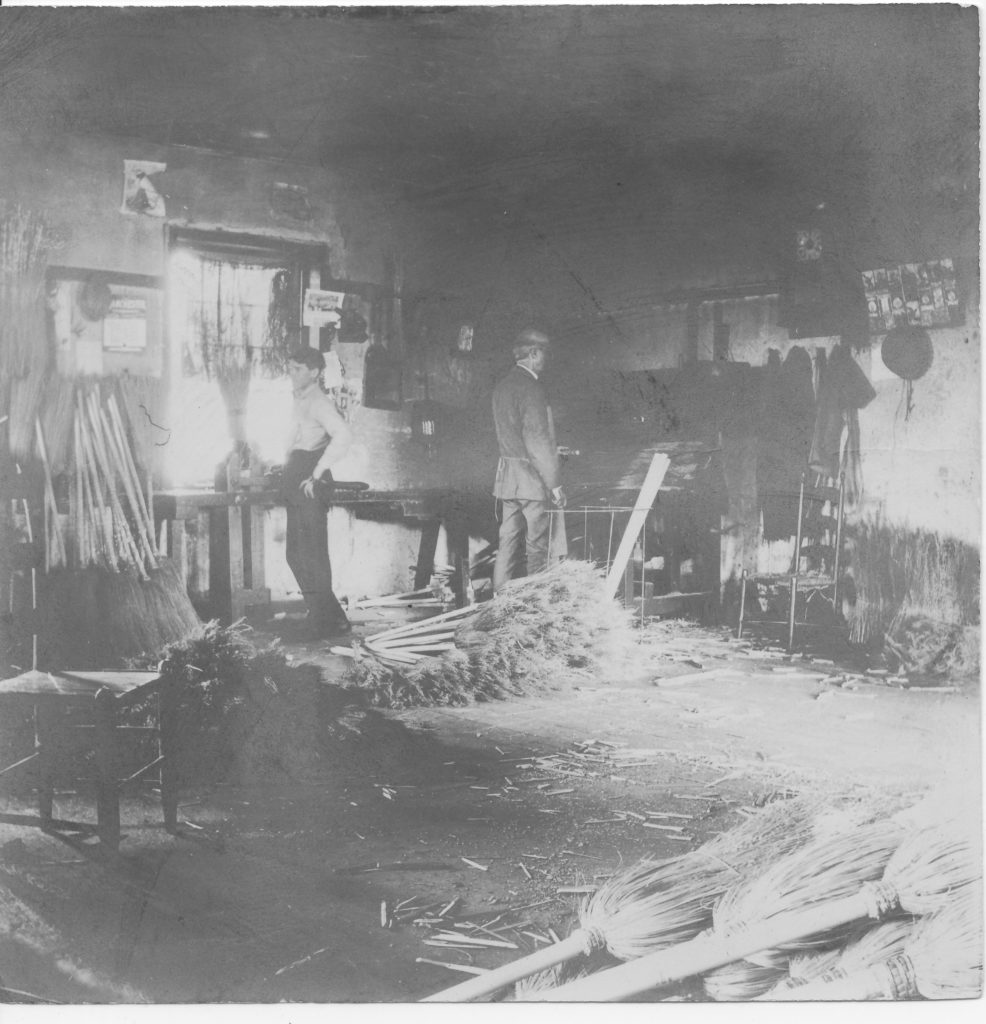

On one hand, as a concentrated community with members who lived in close proximity they were more subject to the quick spread of epidemic illness. On the other hand, however, Pleasant Hill also had members with medical training, and the village grew many of their own medicinal plants.

In addition to outbreaks of infectious diseases such as the measles and cholera, Pleasant Hill also met the same healthcare challenges as all Americans of their day and age. Although many of the treatments provided during the nineteenth century would later prove to be ineffective (if not downright harmful), Pleasant Hill’s trained healthcare staff was vitally important to the overall well-being of the community.

Although hardly the only caregivers at Pleasant Hill, we wanted to highlight the following individuals and share some snippets of their stories.

The Downing Sisters

Three natural sisters who arrived at Pleasant Hill in 1840 as children all later served as nurses at Pleasant Hill. Their names were Eldress Elizabeth Ann Downing, Mary Ann Downing, and Rachel Downing. Although Rachel left the community in 1863, both Elizabeth Ann and Mary Ann remained faithful for the rest of their lives. In addition to serving as a nurse, Elizabeth was also a caretaker of children and worked in the preserve industry.

Dr. John Shain

Shain was an early Shaker convert who served as a physician at Pleasant Hill for 35 years. He promoted healthy eating and a vegetarian lifestyle. Shain was critical of doctors who practiced “heroic” medicine, and he spoke out against calomel, describing the popular mercury-based medicine as poison. Shain lived until the age of 91, and advocated drinking only ice water until the very end.

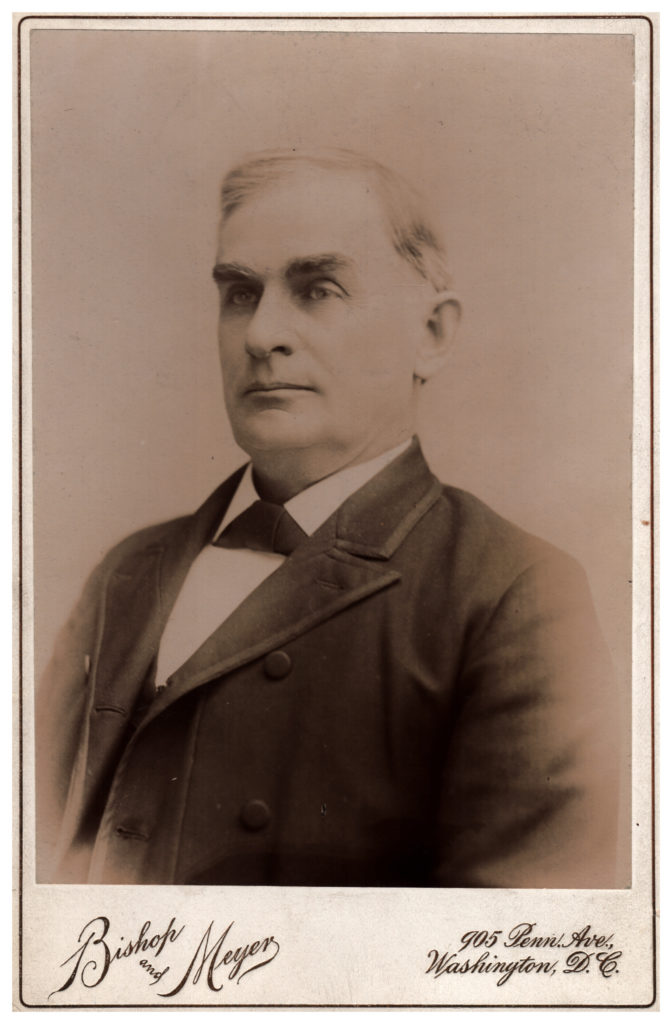

Dr. William F. Pennebaker

Pennebaker arrived at Pleasant Hill as a child in 1849. After expressing an interest in medicine, the Shakers reportedly sent him to Cincinnati for medical and surgical training. Pennebaker authored several nationally published medical articles, and in 1876 he became chief physician at Pleasant Hill. During this time, Pennebaker used his training to care for the community when an influenza epidemic swept through the village in 1892.

Writing to the Shakers’ magazine the Manifesto after the aforementioned influenza epidemic in 1892, Sister Mary Settles gratefully noted “our kind physician and brother, W. F. Pennebaker, has safely carried many patients through La Grippe as well as other ills. We feel thankful that so many of our aged ones have been spared to us.”

Pennebaker served his brethren and sisters faithfully until non-Shaker Dr. J. B. Robards and his wife took over care of the elderly members of the Centre Family in December 1910.