Jacob Glover, PhD., Program Manager

“Indeed, cooking is an art just as much as painting a picture or making a piece of furniture.” – Shaker Eldress Bertha Lindsay, Canterbury, NH. August 1990.

Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill is known today for many wonderful things. From farm animals to hiking trails, guided tours to family-friendly festivals, and Shaker music presentations to bobwhite quail, if you ask ten different people you might get ten different answers of what draws visitors to our property. One item in particular, however, tends to be on everyone’s mind: the food at the Trustees’ Table!

Given the Shaker’s penchant for hospitality, it is no wonder that food has been on the minds of visitors, both invited and uninvited, for over two centuries.

Isaac Newton Youngs and Rufus Bishop, two Shakers visiting from New York in 1834, were offered watermelon so many times during their time at Pleasant Hill that it almost became a running joke in their travel account. All told, they mentioned eating watermelon at least 15 times during their visit—sometimes to the point of indulgence: “Today we have had to attend 3 or 4 times to eating watermelons, and these being pretty good hinders us a good deal.”

A few decades later, thousands of Confederate troops camped-out on the grounds of Pleasant Hill as they traversed central Kentucky in the build-up to the Battle of Perryville in October 1862. The Shakers were moved to pity by the ragged, hungry men, and they gave generously to feed the soldiers. “We nearly emptied our kitchens of their contents and they tore the loaves and pies into fragments and devoured them so eagerly as it they were starving….And then when our stores were exhausted, we were obliged to drive them from our doors while they were begging for food. Heart rending scene!”

In the 1870s, the completion of High Bridge over the Kentucky River brought many tourists to the area near Pleasant Hill. The Shakers offered many of these guests room and board and food service to supplement their declining income in other industries: “Visitors above left early and had to cross the River in Skiffs and walk up to the Towers. Their bill here for entertainment and passage back and forth repeatedly was 50 cents for meals, 40 cents for lodging, and 25 cents passage each way $12.30.”

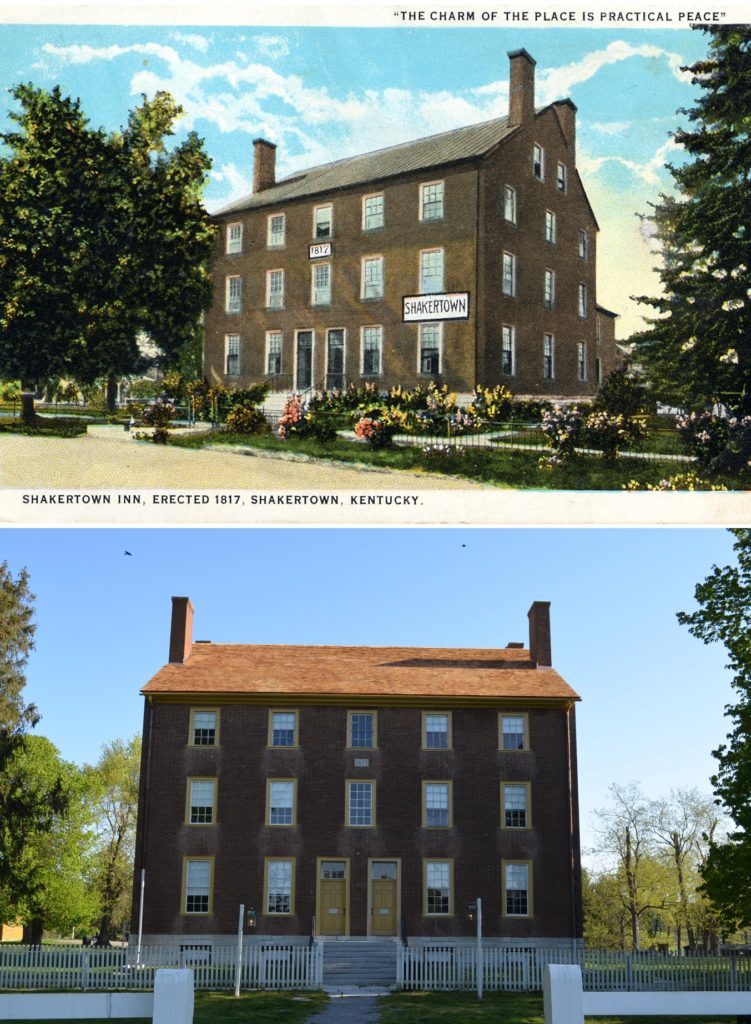

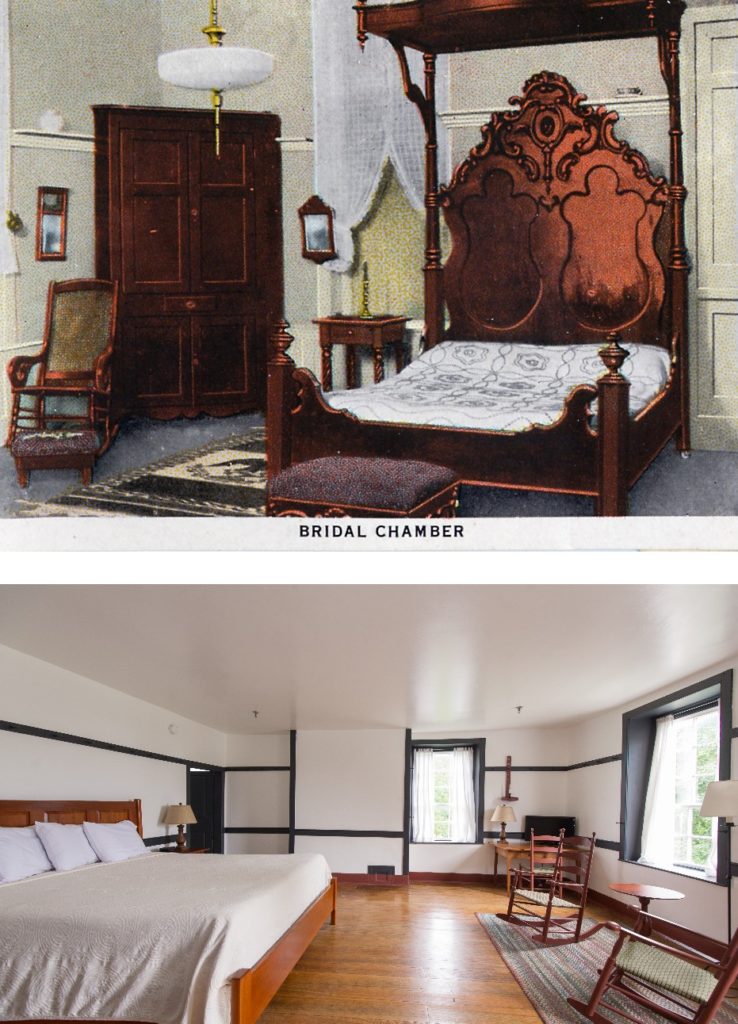

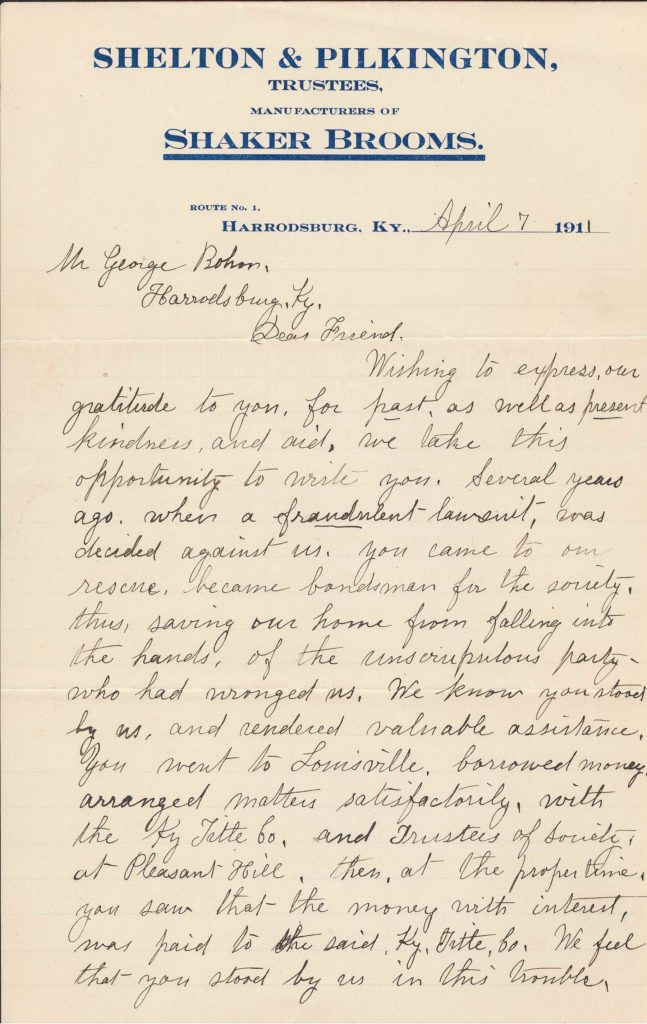

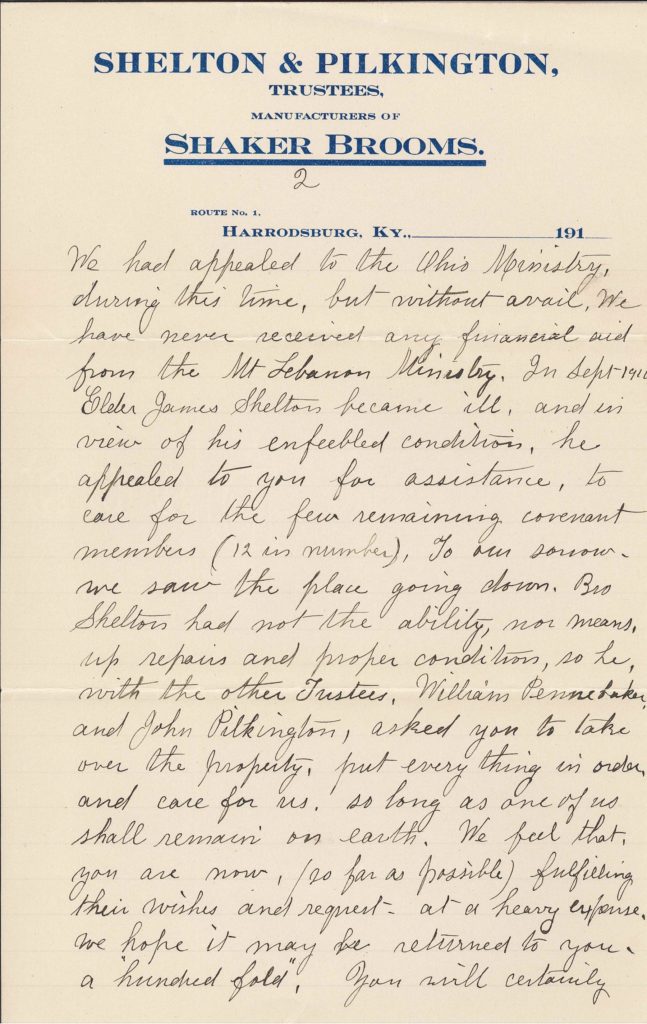

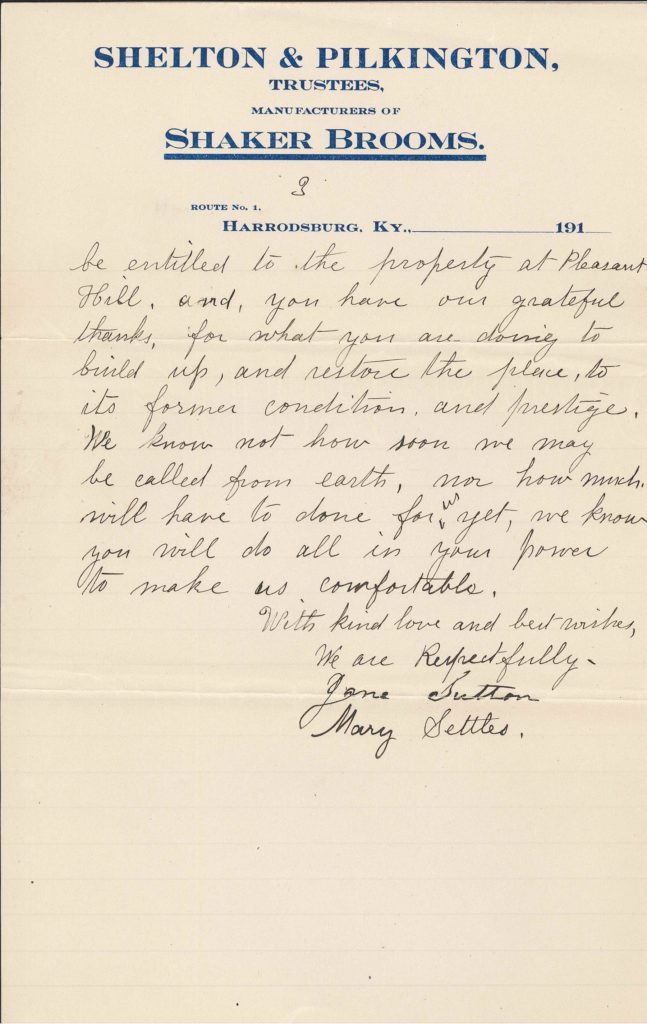

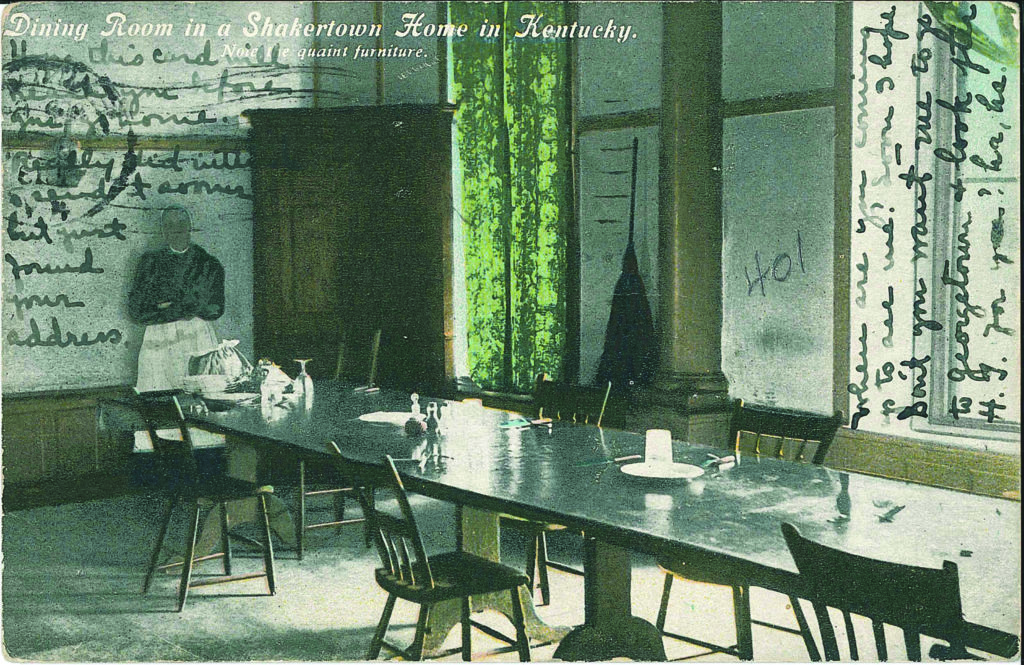

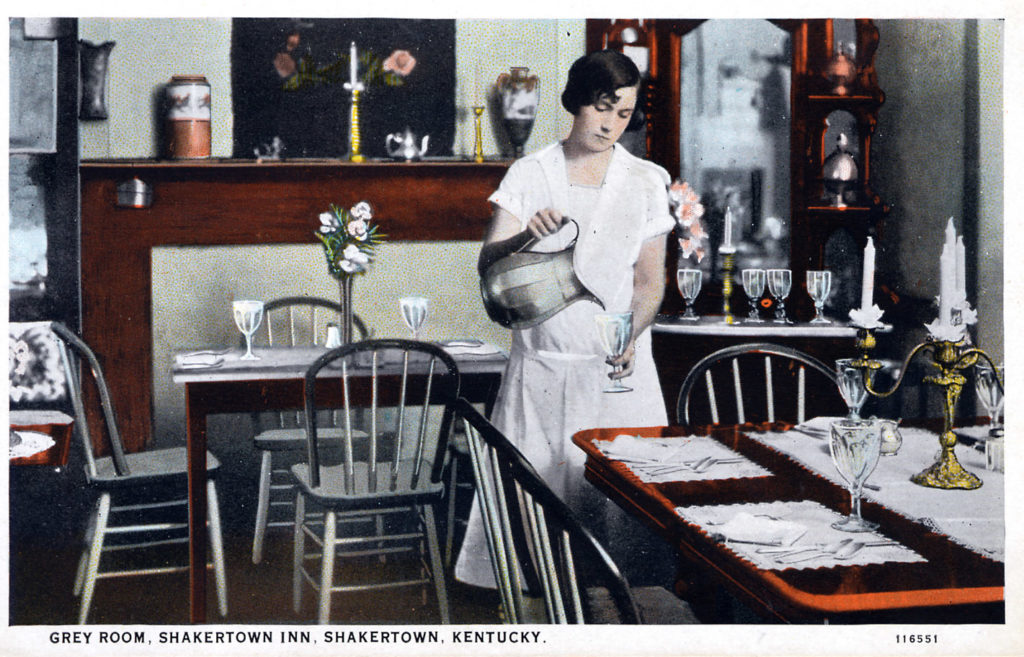

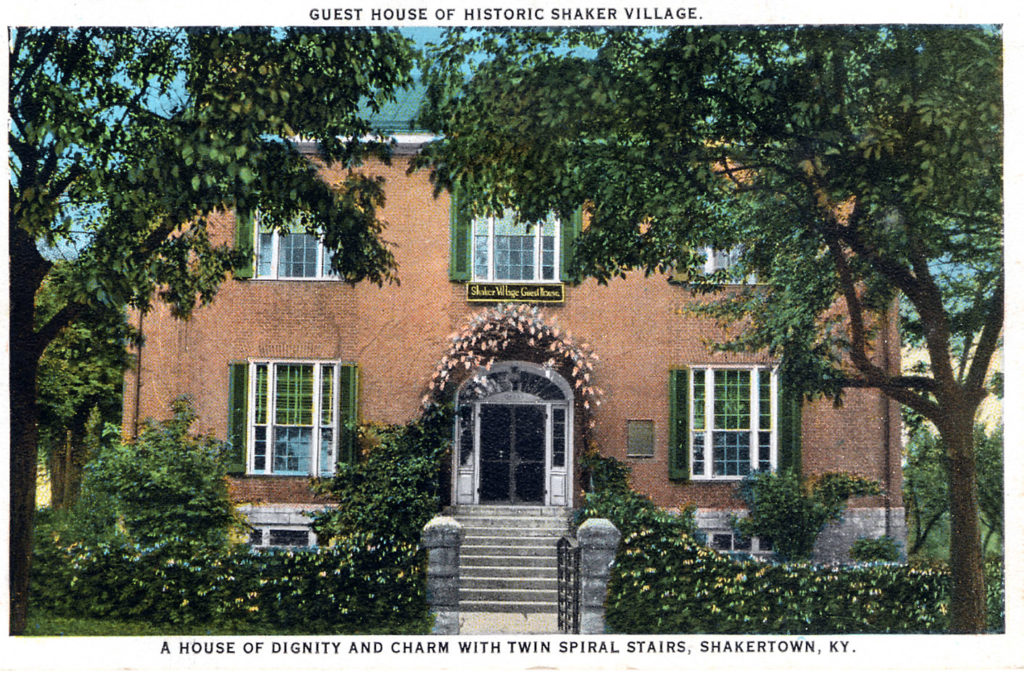

By the late 1800s, some of the buildings at Pleasant Hill had been sold to outsiders who opened hotel and dining establishments. The East Family Dwelling had become the Shakertown Inn by 1897, and the Trustees’ Office had become the Shaker Mary Guest House by the early 1920s.

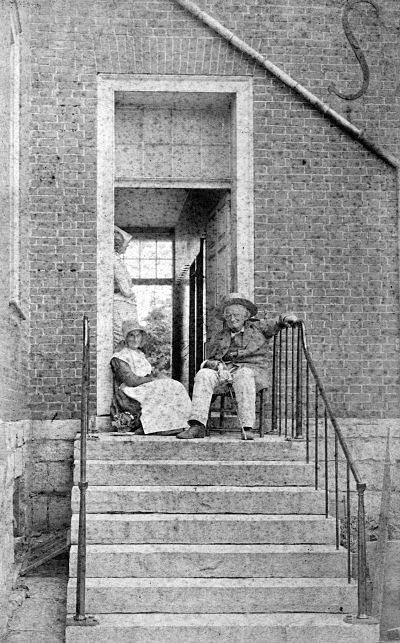

As the years passed, the Trustees’ Office changed hands several more times until it came to be owned by the Renfrew family in the 1950s. Dick DeCamp, a native of Lexington, recalled the restaurant fondly many years later. “The place had a lot of character. It was like something out of a Faulkner novel, going there for dinner. They just had some tables around and the old shades were on the windows….They just had a few things – a special eggplant casserole and fried chicken and old ham.” According to Decamp, guests would sit out on the front steps and “kill a bottle of whiskey” before the food was finally ready. Then, someone would wind up the Victrola and everyone would get to dancing!

Today at Shaker Village we continue this legacy of hospitable service and locally-sourced meals through the Trustees’ Table. The seed-to-table experience at the Trustees’ Table utilizes the best meat and produce from the Shaker Village Farm and other local farms to create our intriguing and delicious seasonal menus. Visit our website to discover all the inspired menu items, beyond our famous lemon pie!